November 26, 2025 – In the dense, fog-draped forests of Pictou County, where ancient pines whisper secrets to the wind, a team of volunteer explorers from the Nova Scotia Ground Search and Rescue (GSAR) has unearthed a cache that could rewrite the heartbreaking saga of missing siblings Lilly Sullivan, 6, and Jack Sullivan, 4. Buried under a tangle of ferns and moss in a remote ravine off Gairloch Road—mere kilometers from the family’s rural home—the discovery includes three weathered all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) registered to Daniel Martell, the children’s stepfather. But it’s not the machines themselves sending chills down investigators’ spines; it’s their cargo: children’s clothing sized for a young girl and boy, a laminated crayon-drawn map labeled “Safe Haven,” and a digital recorder capturing a faint child’s voice reciting a bedtime rhyme. As the RCMP scrambles to connect the dots, one terrifying question looms: Did Martell orchestrate a vanishing act on May 2, 2025, to “protect” Lilly and Jack from perceived dangers, spiriting them deep into the Canadian wilderness where no one could follow?

The Sullivan siblings’ disappearance gripped Canada like a vise five months ago, transforming the quiet hamlet of Lansdowne Station into a media epicenter of grief and suspicion. Lilly, with her shoulder-length light brown hair and infectious giggle, and little Jack, a bundle of energy at just four years old, lived with their mother Malehya Brooks-Murray, stepfather Daniel Martell, and baby sister Meadow in a secluded property hemmed in by thick woods, steep banks, and impenetrable brush. The family had kept the kids home from Salt Springs Elementary on May 1 and 2, citing Lilly’s nagging cough. Surveillance footage from a New Glasgow Dollarama captured the whole clan—mom, stepdad, the two older kids, and Meadow—laughing over snacks at 2:25 p.m. on May 1. That evening, around 10:19 p.m., they returned from groceries, tucking in for what should have been a routine night.

But by 8:00 a.m. on May 2, chaos erupted. Martell and Brooks-Murray claimed they were in the bedroom with Meadow when Lilly popped in and out several times, and Jack’s chatter echoed from the kitchen. By 9:40 a.m., silence. At 10:01 a.m., a frantic 911 call reported the children missing—possibly wandered off into the woods, or worse, snatched by their estranged biological father, Cody Sullivan, amid a bitter custody feud. Cody, who hadn’t seen the kids in three years, was roused at 2:50 a.m. on May 3 for questioning; his alibi held. Initial theories swirled: accidental drowning in a nearby creek, a predatory animal, or simple toddler wandering in the treacherous terrain. Over 160 searchers, drones, and cadaver dogs blanketed four square kilometers in the first days, laying GPS grids and issuing vulnerable missing persons alerts across Pictou, Antigonish, and Colchester counties. By May 7, the ground search scaled back, but the Northeast Nova RCMP Major Crime Unit took the reins under the Missing Persons Act, enlisting aid from New Brunswick, Ontario, the National Centre for Missing Persons, and the Canadian Centre for Child Protection.

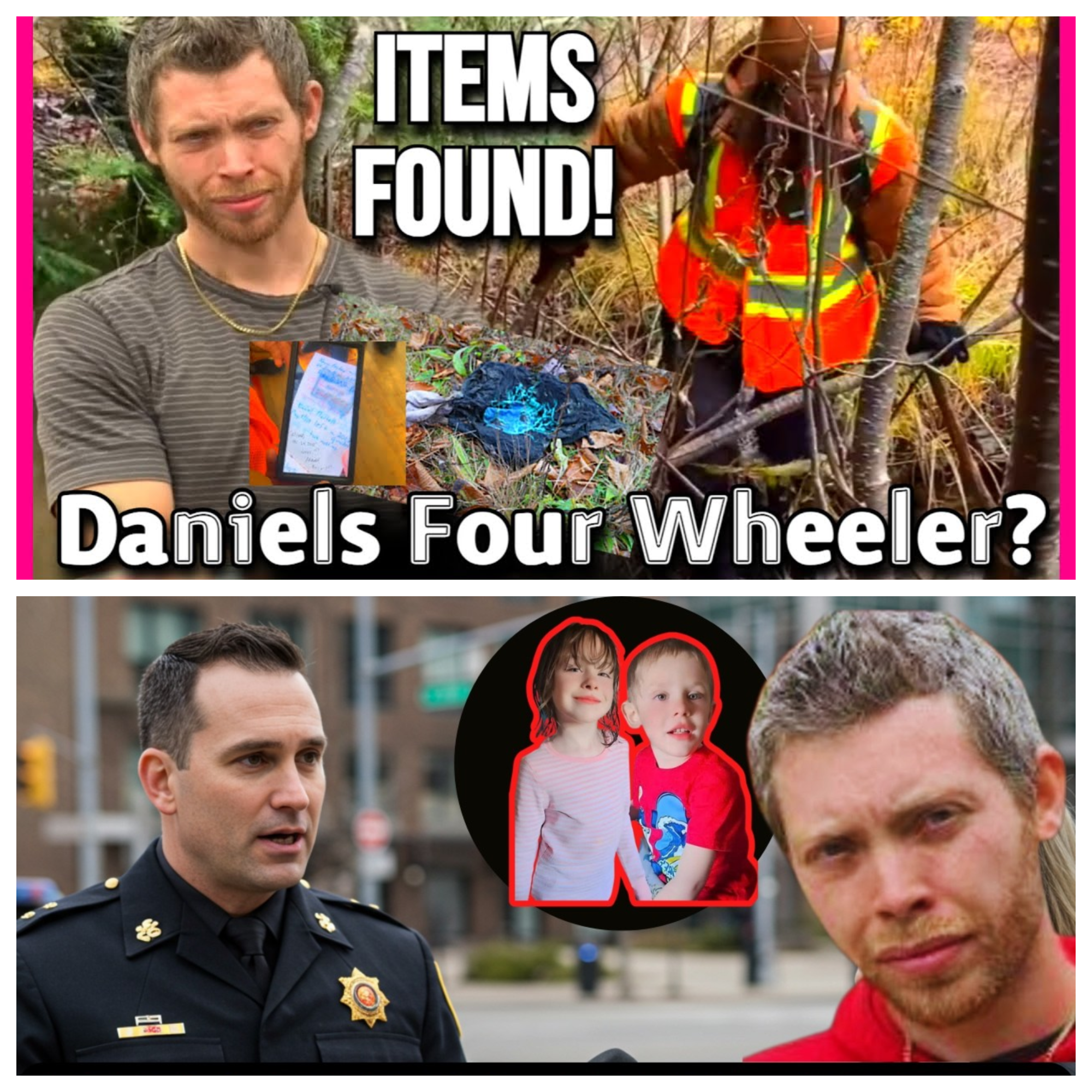

Martell, 35, a burly local handyman with a salt-of-the-earth demeanor, became the face of the family’s anguish. He pleaded publicly on May 6 for tips, even volunteering for a polygraph early on. Brooks-Murray, 28, a devoted mom juggling part-time work, echoed his desperation. Court documents later revealed exhaustive RCMP scrutiny: bank records, phone pings, GPS data from their vehicles—all cleared the couple of criminal involvement by July 16. Witnesses near Gairloch Road reported hearing a vehicle idling oddly in the pre-dawn hours of May 2, but surveillance reviews found no corroboration. Experts dubbed the case “unprecedented,” citing anomalies like the lack of tracks in the soft soil or signs of struggle. “Kids don’t just evaporate,” one child forensic psychologist noted privately. “This feels engineered.”

Enter the ATV bombshell. On October 25, 2025—nearly six months after the vanishing—GSAR volunteers, mapping uncharted ravines for a potential search resumption, tripped over a camouflaged tarpaulin in a sinkhole dubbed “Whispering Gulch.” Beneath it: three Polaris ATVs, mud-splattered and modified with oversized tires, brush guards, and jerry cans for extended off-road treks. VIN numbers traced to Martell, who owned them for “hunting trips,” per old DMV records. But the real gut-punch? The saddlebags and a locked toolbox yielded a trove straight out of a survivalist’s fever dream.

Inside: A sealed bin with neatly folded clothes—a pink unicorn-hooded jacket (Lilly’s favorite, per family photos), Spider-Man pajamas stained with what looks like berry juice (Jack’s go-to sleepwear), size 12T pants and a tiny rain slicker, all monogrammed “L&J.” Two unopened kiddie toothbrushes, a pack of crayons, and a half-used sketchpad with doodles of a “big house in the trees” signed by “Lily + Jackie.” Dominating the find: A laminated 8×10 sheet of construction paper, the “Safe Haven” map, crayoned in vibrant hues. It charts a serpentine path from the Gairloch home, snaking northwest through unmarked trails into the heart of the Cobequid Hills—bypassing highways, skirting ranger stations, and ending at a sketched cabin by a “magic river” (likely the East River John). Adult notations in faded ballpoint: “Slow ride, 2-3 days w/ little feet. Berries here, fish there. No roads = no monsters.” Chillingly, a cheap voice recorder held a 12-second clip: A girl’s soft voice—matching Lilly’s from school videos—murmuring, “Now I lay me down to sleep… keep the bad dreams away till morning,” followed by a boy’s sleepy echo, “Amen, Lily.”

RCMP sources, speaking off-record amid a media blackout, confirm the haul’s authenticity. “This isn’t random junk,” one investigator confided. “It’s a blueprint for going dark.” Behavioral profilers have flipped the script: Martell, scarred by his own custody losses (a sealed 2018 file hints at a dropped child endangerment charge from a prior relationship), may have viewed the Sullivans’ fractured family as a ticking bomb. Cody’s visitation push, Brooks-Murray’s exhaustion, the kids’ coughs—perhaps he saw “rescuing” them as his twisted duty. “He’s not a killer; he’s a ghost-maker,” the profile reads. “Believes the wilds are sanctuary from courts and ‘strangers.'” The ATVs, fueled for 200+ kilometers, could haul a family unit through the hills’ bogs and thickets, invisible to aerial scans under the canopy.

Brooks-Murray’s reaction was visceral. At a tense presser outside the family home—now a shrine of faded posters and wilting teddy bears—she clutched a photo of Lilly’s bangs and Jack’s dimples, tears streaming. “That’s my girl’s voice. Daniel didn’t hurt them—he erased us. He’s out there, teaching them to hide from me.” Martell, who hasn’t spoken publicly since May, vanished from radar post-discovery; his phone went dark, truck impounded. Cody Sullivan, cleared but bitter, fumed to reporters: “If he’s got my kids, it’s over my dead body.” The family rift deepens the wound—grandparents on both sides feud over blame, while baby Meadow, now 20 months, babbles “Wiwy” at empty swings.

With winter’s icy grip looming—first snow flurries dusted the hills November 20—the RCMP mobilizes a frantic push. Ground-penetrating radar sweeps the map’s route, FLIR drones pierce the dusk, and scent dogs (live-trail specialists this time, no cadavers) fan out from the cache. Judicial warrants fly for Martell’s bank remnants and a dusty storage locker in New Glasgow. “We’re treating this as flight, not foul play,” RCMP Staff Sgt. Curtis MacKinnon stated November 25. “But time’s our enemy. Six months off-grid? Those kids could be fluent in forest lore, calling him ‘Pops’ by a campfire.”

The “Safe Haven” map taunts from evidence photos splashed across CBC and CTV: That cabin sketch—does it match a derelict trapper’s shack in the hills? Online sleuths swarm X with theories—Martell in cahoots with a Mi’kmaq off-grid commune? Polaroids from his locker showing the kids on “hikes”? Yet anomalies persist: No ransom, no sightings, just echoes. As searchlights carve the November night, one truth cuts deep: In Canada’s vast wilds, love can curdle into captivity. Lilly and Jack Sullivan aren’t just missing—they’re mythologized, perhaps thriving in shadows Martell built to last. Until a boot print or a child’s cry breaks the silence, hope flickers like a lantern in the brush. Call the tip line: 902-896-5060. Because in Pictou County’s green maze, every trail might lead home—or to a forever hideaway.