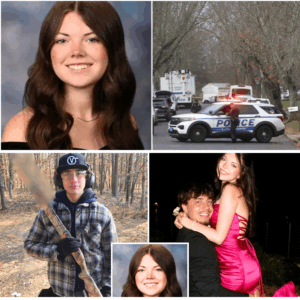

Eternal Crown: The Heartbreaking Homecoming of Carson Ryan, Iowa’s Fallen Star

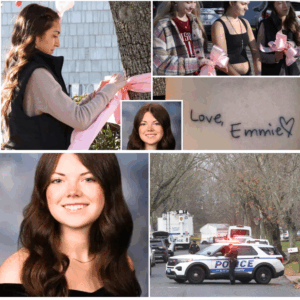

In the amber glow of an Iowa autumn, where cornfields whisper secrets to the wind and Friday night lights pierce the rural dusk like beacons of youthful promise, the small town of Washington found itself enveloped in a profound, aching sorrow. It was the evening of October 2, 2025, in the echoing auditorium of Washington High School, when the air grew thick with unspoken grief. The Homecoming ceremony, usually a riot of cheers, confetti, and teenage exuberance, unfolded under a pall of black and orange—the school’s colors, now symbols of a void too vast to fill. As the principal’s voice cracked over the microphone, announcing the winners, a hush fell deeper than any silence before. Iris Dahl, a poised senior with tears carving silent paths down her cheeks, was crowned Homecoming Queen. Beside her, on an empty throne draped in velvet, sat not a living classmate, but a framed photograph: Carson Ryan, 17, his easy grin frozen in time, a paper crown perched jauntily on the frame as if he’d just stepped off the field. Posthumously crowned Homecoming King, Carson’s spirit presided over the night, a poignant testament to the boy who had touched every corner of his community in ways no trophy ever could.

Less than a week earlier, on the crisp morning of September 27, Carson’s world—and Washington’s—had shattered irreparably. What began as a routine squirrel hunt in the wooded fringes of rural Brighton, just a short drive from the town’s quaint Main Street lined with family-owned shops and American flags fluttering in the breeze, ended in a tragedy so swift and senseless it defied comprehension. Carson, a varsity football player whose number 80 jersey had become a talisman on the gridiron, was out with a group of fellow hunters, shotguns slung over shoulders, the earthy scent of fallen leaves mingling with the sharp tang of gun oil. Laughter echoed among the trees as they tracked their quarry, the sun filtering through the canopy in dappled patterns that played tricks on the eyes. But in a heartbeat, illusion turned fatal. As Carson rose from his crouch to reposition, his silhouette blurred by shadows and swaying branches, another hunter—part of their tight-knit party—mistook him for the furtive rustle of a squirrel. A single shot rang out, striking the back of his head with merciless precision. Carson crumpled, the forest’s symphony falling silent around him.

Paramedics raced him to the University of Iowa Health Care Medical Center in Iowa City, sirens wailing through the rolling hills of Washington County, but the damage was irrevocable. Pronounced dead at the scene’s shadow, Carson’s passing left a family, a school, and a community reeling. The Iowa Department of Natural Resources (DNR) confirmed the details in a somber press release two days later, emphasizing the accidental nature of the incident. Captain Shawn Meier, head of the agency’s law enforcement bureau, stood amid the investigation’s early chaos, his voice steady but laced with the weight of inevitability. “Hunting accidents are tragic, and you wish you could bring them all back,” Meier told reporters from KCRG-TV, his eyes scanning the treeline where forensics teams combed for clues. Sunlight had pierced the foliage erratically that afternoon, casting long shadows that danced with the wind’s subtle movements. “You have other types of movement—wind, animals stirring in the underbrush,” Meier explained, underscoring a timeless hunter’s creed: Identify your target beyond doubt. No charges were anticipated, the DNR stressed; this was no malice, but a confluence of misfortune in a pursuit Carson himself adored. The investigation, involving the Washington County Sheriff’s Office, wrapped swiftly, ruling it an unequivocal accident—a small mercy in an ocean of loss.

Washington, Iowa—a town of 7,000 souls nestled in the southeastern corner of the state, where the Skunk River meanders lazily past historic brick facades and family farms stretch toward the horizon—mourned as one. Founded in 1839, it’s the kind of place where neighbors wave from porches and high school sports bind generations like threads in a quilt. Washington High School, with its red-brick halls and Demon mascot roaring from banners, stands as the community’s beating heart. Carson was woven deep into its fabric: a senior whose laughter echoed in hallways, whose determination on the basketball court inspired underclassmen, and whose quiet faith anchored Bible studies after practice. When news broke, the shock rippled outward like a stone in still water. Vigils sprang up overnight—candles flickering on the steps of the First Baptist Church, where Carson had been an active youth member, their flames mirroring the stars above. Social media overflowed: #RIPCarson80 trended locally, posts from teammates sharing grainy videos of his tackles, coaches penning odes to his work ethic. “He was the glue,” Assistant Football Coach Nic Williams said at a Sunday evening vigil, his voice breaking as he recalled Carson leading weekly devotionals. “A fierce competitor who lifted everyone around him.”

The days leading to Homecoming blurred into a tapestry of tributes, each thread a deliberate act of remembrance. Black and orange T-shirts, emblazoned with Carson’s number 80 in bold white script, proliferated like wildflowers after rain. Custom-printed by local shops on Main Street, they sold out within hours, worn to pep rallies, parades, and bonfires. Hand-painted signs adorned storefront windows: “We Love You, Carson—Forever a Demon King,” one read in looping cursive, hearts dotting the i’s; another, on the local hardware store’s glass, depicted a football soaring toward heaven, captioned “Catch You Later, #80.” The Main Street Washington Facebook page, a digital town square, buzzed with photos—families posing in the shirts, cars draped in orange streamers honking in solidarity. Neighboring Pekin Community Schools, just miles away, urged students and staff to don the colors on September 29, a ripple of empathy crossing district lines. “Our hearts are with the Washington High School community,” their statement read, a simple gesture that swelled into a wave of shared sorrow. Even the Washington Demons’ track and field team, where Carson had sprinted his way to personal bests, posted a heartfelt tribute: “Keep Carson’s mom, family, classmates, and teammates in your hearts… Our hearts are broken. LGD.”

To know Carson Ryan was to witness unfiltered joy wrapped in quiet strength—a boy whose obituary painted him not as a victim, but a vibrant force of nature. Born on a spring day in 2008 to Heidi Wheeler and her family in Washington, Carson grew up knee-deep in the outdoors, his world a canvas of rivers, fields, and endless skies. Fishing lines tangled in his fingers before he could tie his shoes; hunting rifles became extensions of his curiosity by middle school. “He loved the thrill of the chase, the peace of the wild,” his family wrote, evoking a teen who could spend hours casting into the Iowa River, debating the merits of nightcrawlers versus minnows with his dad. At Washington High, he channeled that energy into athletics: a standout in basketball, where his crossover dribble left defenders grasping air; track and field, his long strides eating up the oval; and football, his rookie season on the varsity squad marked by bone-crushing tackles and sideline cheers. Teammates remember him not for stats—though his 40-yard dash clocked an enviable 4.7—but for the post-game huddles, where he’d crack jokes to ease the sting of losses.

Faith was Carson’s compass, a steady north in a whirlwind life. A devoted member of the First Baptist Church, he volunteered at youth camps, his Bible underlined with verses on perseverance: “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.” At the YMCA, where he lifeguarded and coached pee-wee soccer, kids idolized him—the big brother who taught free throws with infinite patience, turning drills into games of “horse” under the gym’s fluorescent hum. Academically, he was no slouch: straight-A student eyeing the University of Northern Iowa, where he dreamed of a degree in accounting, blending his love for numbers with a knack for helping friends budget their allowance. “Carson was a friend to all,” his obituary proclaimed, a simple truth echoed in the stories pouring from classmates. One girl, a shy freshman he’d tutored in algebra, shared on Instagram: “He made equations feel like adventures. Now, life’s equation without him? Unsolvable.”

The accident’s shadow loomed large, a stark reminder of hunting’s double-edged sword in the heartland. Iowa’s woodlands, teeming with whitetail deer and game birds, draw thousands annually—over 100,000 hunters in 2024 alone, per DNR stats. Yet, mishaps persist: 15 incidents in 2023, two fatal, often from misidentification in low light or dense cover. Carson’s case, unfolding in the golden hour’s deceptive haze, underscored the peril. Meier’s post-incident plea resonated: “Always, always confirm your target. A second’s glance can save a life.” Conservation officers canvassed the site, interviewing the group—friends and family, their faces ashen with guilt and grief. No foul play, no negligence beyond the tragic error; just the unforgiving math of motion and mirage. For Carson’s hunting party, the woods that once promised camaraderie now echoed with what-ifs, a chorus that would haunt campfires for years.

Homecoming Week, serendipitously timed, became catharsis amid catastrophe. Carson had been nominated to the court weeks earlier, his popularity a given—votes tallied in secret ballots during lunch periods, whispers of “Carson’s got this” floating like autumn leaves. When the accident struck, the school pivoted with grace: counselors on hand, assemblies laced with his highlights reel. The parade down Main Street featured a float dedicated to him—a mock football field with his jersey draped over a goalpost, riders in black-and-orange pom-poms chanting his name. Pep rallies swelled with chants of “Ryan! Ryan!” the gymnasium’s rafters shaking as if he’d dashed onto the court one last time. And the crowning: Iris Dahl, ascending the stage in a gown of shimmering gold, placed the crown on Carson’s photo herself, her sobs mingling with applause that thundered like a standing ovation from heaven. “He deserved this,” she whispered to reporters from the Southeast Iowa Union, dabbing her eyes with a tissue monogrammed with #80. The audience—parents in bleachers, teachers misty-eyed—rose as one, a sea of orange rising in waves.

Heidi Wheeler, Carson’s mother, navigated the maelstrom with a mother’s unyielding poise. A single parent in a town where family ties run deep, Heidi worked as an administrative assistant at the local hospital, her days a blur of charts and compassion. Carson was her anchor, her co-pilot in carpools and county fairs. The GoFundMe launched by a close friend—titled “Supporting Heidi and Family in Memory of Carson”—exploded with generosity, surpassing $57,000 by week’s end. “Our dear friend Heidi is facing an unimaginable tragedy,” the organizer wrote, words that captured the raw ache. “No parent should endure this… His kindness, humor, and genuine spirit touched countless lives, leaving an immeasurable void.” Donations trickled from afar—alumni in Chicago, hunters in Minnesota—each note a balm: “Carson coached my son; he was a gift.” Heidi, in rare glimpses to media, spoke of her boy’s light: “He’d want us laughing through the tears, planning the next adventure.” Her siblings and extended kin rallied, filling the Wheeler home with casseroles and quiet vigils, the scent of homemade pie mingling with the faint echo of Carson’s cologne.

The funeral on October 6, at First Baptist, drew hundreds—townsfolk spilling onto the lawn, folding chairs under a crisp blue sky. Pastor Elias Grant eulogized Carson as “a shepherd in cleats,” weaving tales of his Bible study insights with gridiron grit. The service program, edged in orange, featured a collage: Carson mid-tackle, rod in hand at dawn, grinning with YMCA tots. A youth choir sang “It Is Well,” voices trembling but true, as pallbearers—teammates in letterman jackets—carried the casket, Carson’s football tucked beneath his arm like a final playbook. Burial followed at Washington City Cemetery, a plot shaded by maples turning fiery red, his headstone to bear “Beloved Son, Eternal Competitor.”

In Washington’s wake, Carson’s legacy blooms eternal. The Demons’ next game? A shutout victory, #80 painted on helmets, fans unveiling a banner: “Play Like Carson.” Youth programs at the YMCA now bear his name, scholarships seeded for accounting majors at UNI. Hunting safety workshops, hosted by DNR at the community center, draw overflow crowds—Captain Meier leading sessions on visibility vests and target verification, Carson’s photo a gentle sentinel. “He’d hate for another family to hurt like this,” a participant confides, echoing the town’s resolve.

Yet, beneath the tributes lies a deeper reflection: the fragility of joy in fleeting years. Homecoming, that quintessentially American rite—parades, kings, queens—crystallizes youth’s zenith, a week where small-town dreams swell under stadium lights. For Washington, it became a requiem and resurrection, Carson’s crown a bridge from earth to eternity. Iris Dahl, reflecting post-ceremony, summed it: “He wasn’t just king; he was our heartbeat.” As October’s harvest moon rises over Iowa’s prairies, Washington’s lights flicker on, games resume, lives inch forward. But in every cheer, every cast line, every prayer, Carson Ryan reigns—crowned forever in the hearts he forever claimed.

This story, raw and resonant, reminds us: Life’s fields are fraught, but love’s harvest endures. In the heartland’s quiet cadence, a boy’s light defies the dusk.