The families of the four University of Idaho students murdered in 2022 have filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Washington State University (WSU), accusing the institution of gross negligence that they claim directly contributed to the preventable killings.

On January 7, 2026, attorneys representing Steve Goncalves (father of Kaylee Goncalves), Karen Laramie (mother of Madison Mogen), Jeffrey Kernodle (father of Xana Kernodle), and Stacy Chapin (mother of Ethan Chapin) submitted the complaint in Skagit County Superior Court, Washington. The suit alleges that WSU ignored at least 13 documented reports of threatening, stalking, harassing, or predatory behavior by Bryan Kohberger during the fall 2022 semester—behavior directed primarily at female students and staff in the criminology department where he worked as a teaching assistant.

The core of the allegations is stark: WSU possessed the authority—and the obligation—to investigate and remove Kohberger from campus long before the November 13, 2022, stabbings. Instead, according to the lawsuit, the university failed to act, allowing a dangerous individual continued access to campus housing, salary, tuition waivers, health benefits, and proximity to the crime scene just eight miles away in Moscow, Idaho.

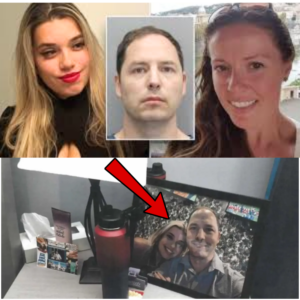

The victims—Ethan Chapin (20), Madison Mogen (21), Xana Kernodle (20), and Kaylee Goncalves (21)—were found stabbed to death in an off-campus rental house on King Road. The attack was savage: throats slashed, defensive wounds indicating fierce struggles, bodies discovered in bedrooms by surviving roommates who had been asleep downstairs. The small college town of Moscow was plunged into terror, and the subsequent months-long manhunt gripped the nation.

Kohberger, then a 28-year-old Ph.D. student in WSU’s Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology, was arrested on December 30, 2022, at his parents’ home in Pennsylvania. Evidence against him included:

DNA from a Ka-Bar knife sheath left on a bed next to one of the victims, matched through investigative genetic genealogy.

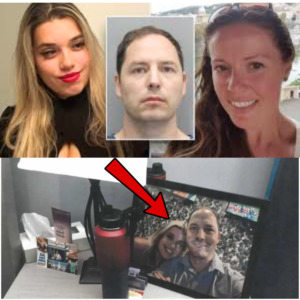

Cellphone records showing his device connected to a tower near the crime scene at least twelve times in the months leading up to the murders, including multiple visits on the night of the killings and a return trip hours later.

Surveillance footage of his white Hyundai Elantra circling the neighborhood in the early morning hours of November 13.

After more than two years of pretrial motions, venue disputes, and death-penalty negotiations, Kohberger entered guilty pleas on July 23, 2025, to four counts of first-degree murder and one count of burglary. In exchange for avoiding execution, he received four consecutive life sentences without the possibility of parole at the maximum-security Idaho State Correctional Institution.

For the families, however, the criminal conviction was insufficient. The civil suit seeks to hold WSU accountable for what they describe as systemic failures in threat assessment, Title IX compliance, and campus safety protocols.

The complaint details how WSU allegedly received repeated formal complaints about Kohberger’s conduct throughout the fall semester. These reports, the plaintiffs argue, should have triggered immediate intervention under the university’s own policies on student and employee misconduct, sexual harassment, stalking, and workplace violence. Instead, the school purportedly did nothing meaningful—no suspension, no removal from teaching duties, no referral to law enforcement, no heightened monitoring.

“These murders were foreseeable and preventable,” the lawsuit states repeatedly. By failing to act on credible reports of escalating predatory behavior, WSU is accused of breaching its duty of care to the broader community—including students at neighboring institutions like the University of Idaho.

The suit invokes Title IX, the federal law prohibiting sex-based discrimination in education, arguing that WSU created or tolerated a hostile environment by ignoring complaints of gender-based harassment and stalking. It also claims violations of common-law duties of reasonable care and negligent supervision.

Legal analysts view the case as potentially strong. Civil cases require only a preponderance of evidence (“more likely than not”), a far lower bar than the criminal standard of beyond a reasonable doubt. Discovery could force WSU to produce internal emails, incident reports, threat-assessment committee minutes, Title IX coordinator notes, and personnel files—materials that might reveal whether officials knowingly downplayed risks to protect the university’s reputation or avoid liability.

Robert Clifford, a Chicago-based plaintiffs’ attorney not involved in the case, told Fox News that leaving the damages amount unspecified is a deliberate tactic. “It keeps the focus on liability rather than dollar signs at this stage and allows a jury to decide the full value after hearing all the evidence,” he explained. He also noted that Kohberger’s guilty plea, while powerful in the public mind, may not be admissible against WSU; the university can still attempt to shift all blame to him personally. However, the differing burdens of proof weaken that defense significantly.

This is not the first time institutions connected to the case have faced civil liability. In 2024, the University of Idaho settled with the Goncalves family for $1 million over claims of inadequate security at the King Road house. That agreement included commitments to improve campus safety measures. Now WSU—a much larger public university—faces potentially far greater financial exposure, along with intense reputational damage.

WSU has not yet filed a formal response. University spokespeople have previously emphasized that campus police and student conduct offices follow established protocols and that no criminal charges were ever filed against Kohberger while he was enrolled. But the lawsuit directly challenges that narrative, alleging those protocols were ignored or inadequately enforced.

The human cost remains the most wrenching aspect. Steve Goncalves has spoken publicly about the daily agony of losing Kaylee, describing her as the family’s “light” and vowing to pursue every avenue for accountability. Karen Laramie has shared memories of Madison’s boundless optimism and adventurous spirit. Jeffrey Kernodle remembers Xana’s fierce loyalty and athletic energy. Stacy Chapin continues charitable work in Ethan’s name, honoring a son who loved the outdoors and brought joy to everyone around him.

These parents are not merely plaintiffs; they are grieving families refusing to let institutional inaction erase their children’s stories. The lawsuit is a demand for transparency: What did WSU know? When did they know it? Why didn’t they act?

If the case proceeds to trial, jurors may hear testimony from former students who filed complaints, from department chairs who reviewed them, from Title IX coordinators who allegedly failed to escalate, and possibly even from surviving roommates whose lives were forever altered that night.

Beyond the courtroom, the suit raises urgent questions for higher education nationwide. How rigorously do universities vet and monitor graduate assistants in sensitive fields like criminology? How seriously are stalking and harassment reports treated when the accused is an employee rather than a student? In an era of active-shooter drills and Title IX tribunals, can institutions still claim ignorance when multiple red flags accumulate?

For the Moscow-Pullman community, the scars remain raw. Memorials dot the landscape, vigils continue, and the once-carefree rhythm of college life carries an undercurrent of caution. The King Road house has been demolished, replaced by an empty lot that serves as a silent reminder.

As this civil battle begins, the families of Ethan, Madison, Xana, and Kaylee carry forward their fight—not for vengeance, but for prevention. They want assurance that no other set of parents will ever receive the same devastating knock at the door because a university chose silence over safety.

The coming months of litigation will likely reveal painful truths about what was known, what was ignored, and what might have been done differently. For four young lives cut short and the families left behind, those truths cannot come soon enough.