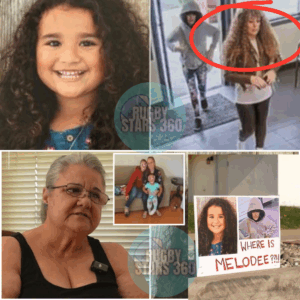

The white 2024 Chevrolet Malibu hummed down Interstate 15 like a phantom in the desert dusk, its California plates glinting under the relentless Arizona sun one moment—and vanished the next. Inside, 9-year-old Melodee Buzzard clutched her stuffed unicorn, her brown curls tucked under a straight black wig, her wide eyes reflecting the endless horizon. Her mother, Ashlee Buzzard, 35, gripped the wheel with white knuckles, glancing in the rearview not for traffic, but for ghosts. What started as a seemingly innocuous road trip on October 7, 2025, has morphed into a chilling odyssey of deception, with Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s investigators now revealing a damning detail: Ashlee swapped the car’s license plates mid-journey, a calculated move they believe was designed to “avoid detection” and throw any pursuers off the scent.

This bombshell, unveiled in a packed press conference at the Lompoc Sheriff’s substation yesterday afternoon, has transformed the search for Melodee from a routine missing-child alert into a high-stakes manhunt spanning five states. Sgt. David Zick, his badge gleaming under fluorescent lights, laid it bare: “We’re not dealing with a panicked parent here. Swapping plates requires tools, time, and intent. This was premeditated evasion, and it puts Melodee’s safety in even graver peril.” As cadaver dogs sniff the sagebrush along Utah’s remote highways and FBI drones buzz over Colorado’s high plains, the revelation has shattered the fragile hope of Melodee’s relatives and riveted a nation already weary from too many Amber Alerts. Where is Melodee? And what dark secrets propelled her mother to turn a family getaway into a fugitive’s flight?

In the quiet cul-de-sacs of Vandenberg Village, where rocket launches punctuate the sky and families grill under eucalyptus trees, the Buzzard household was once a picture of suburban normalcy. But dig beneath the surface, and the cracks appear like fault lines in the California earth. Ashlee, a former paralegal whose career fizzled after a string of personal setbacks, had been raising Melodee alone since the tragic death of Melodee’s father, Rubiell Meza, in a 2016 car crash on Highway 101. Rubiell, a beloved auto mechanic with a garage full of dreams, left behind a void that Ashlee filled with fierce protectiveness—or, as relatives now claim, suffocating control.

“Melodee was her everything,” says Lori Miranda, Ashlee’s 58-year-old mother and Melodee’s grandmother, speaking from her Santa Maria bungalow where faded photos of a toddler Melodee adorn the mantel. “But after Rubiell, Ashlee changed. She pulled away from everyone—me, his family, even old friends. It was like she was building walls around them.” Court records echo this isolation: Ashlee fought Rubiell’s relatives for full custody in 2017, citing “emotional instability” on their side, and won. By 2020, visits dwindled to holidays, then nothing. Bridgett Truitt, Rubiell’s 42-year-old sister and a nurse in Oxnard, recalls the last time she saw Melodee: a tense Easter egg hunt in 2021, where the girl clung to Ashlee like a shadow. “Ashlee hovered, whispering in her ear. Melodee barely spoke. We begged for more time, but Ashlee said, ‘She’s fragile. She needs routine.’ Routine? It was a cage.”

That cage extended to education. Pulled from Lompoc Elementary in third grade amid “bullying complaints,” Melodee entered the district’s independent study program in fall 2023. Homeschool logs show spotty progress: a diorama on California missions, a book report on Charlotte’s Web. But by summer 2025, submissions ceased. Teachers flagged it; Ashlee responded with excuses—illness, vacations. A September welfare check by Child Protective Services found nothing amiss: Melodee “playing in her room,” Ashlee cooperative. But hindsight paints a different portrait. Neighbors whisper of drawn blinds, rare outings, and Ashlee’s growing paranoia—installing Ring cameras, changing locks. “She’d wave hello, but her eyes said ‘stay away,'” says next-door retiree Hank Ellis, 67, who last saw Melodee riding a scooter in August, her laughter echoing like a memory.

Financial strain loomed too. Ashlee’s paralegal job ended in 2022 amid layoffs; freelance gigs barely covered the $1,800 rent. Creditors circled: a $15,000 judgment from a 2024 lawsuit over unpaid medical bills, $8,000 in credit card debt. Relatives offered help; Ashlee rebuffed them. “She said she had it handled,” Miranda recalls. “But I saw the stress lines on her face. Melodee picked up on it—asking why Mommy was sad.” Was debt the spark? Or something sinister? Ashlee’s browser history, seized from her laptop, hints at desperation: searches for “quick cash loans no credit check” (September 15), “best states for starting over” (September 28), “how to disappear legally” (October 1).

The trip ignited on October 7. At 9:45 a.m., Ashlee pulled into Lompoc’s Enterprise Rent-A-Car, credit card in hand. Footage shows her signing for the white Malibu—plate 9MNG101—while Melodee fidgeted nearby, backpack slung over one shoulder. “They seemed excited,” clerk Maria Gomez told investigators. “Mom mentioned ‘visiting family out east.'” By noon, they were on Highway 101 north, GPS pings charting a meandering path: a Starbucks stop in Buellton (12:17 p.m., venti latte and a cake pop), a picnic at Lake Cachuma (1:45 p.m., per a witness who snapped a photo of Melodee feeding ducks).

Day two veered east. Crossing into Arizona via I-15, the Malibu clocked at a Kingman rest area at 3:17 p.m.—still California plates. But by 4:22 p.m. in St. George, Utah, cameras captured New York tag HCG9677. “It’s a classic dodge,” explains retired LAPD detective Mark Hale, consulted by this outlet. “Rest stops are blind spots—no cams, lots of parked rigs. You unscrew plates with a multi-tool, swap ’em quick. Takes two minutes if you’re practiced.” The swapped plate? Traced to a stolen 2019 Honda Civic in Buffalo, NY—lifted in July, likely fenced on the black market. “Ashlee didn’t steal it herself,” Zick clarified. “But acquiring it? That’s premeditation.”

Why Utah? The route hugs remote highways: US-89 through Kanab, past Zion’s crimson cliffs, then east on US-40 toward Colorado. Stops multiply: a Panguitch diner (October 8, 8:09 p.m., burgers and fries, Melodee coloring a placemat); a Green River motel (October 9, check-in 6:42 a.m., single room, cash paid). Surveillance evolves too: By Panguitch, both wear wigs—Ashlee’s a blonde flip, Melodee’s the straight black that obscures her curls. “Disguises plus plates? That’s not tourism,” FBI Agent Lena Torres said on Fox News. “That’s flight.”

The final frame: October 9, 10:37 a.m., a Valero station on the Colorado-Utah border. Melodee, hood up, sips a blue Slurpee; Ashlee fuels up, scanning the lot like prey. The Malibu rolls east—then nothing. No pings in Colorado’s Moffat County, no tolls in Nebraska’s Panhandle. Ashlee resurfaces alone in Lompoc on October 10, returning the car at 6:18 p.m. “Great trip,” she told Gomez, plates restored. Melodee? “With relatives.” But relatives were clueless. Truitt got the call from deputies October 14: “Melodee’s missing. Ashlee says she’s safe, but won’t say where.”

The investigation exploded. Welfare checks escalated to searches; the FBI joined October 22, classifying Melodee “endangered.” Warrants hit: Ashlee’s home yielded the unicorn backpack—empty—and a storage unit with wigs, passports (expired), and $2,300 cash. The Malibu’s black box confirmed the route; forensics found Melodee’s fingerprints on the passenger door, a candy wrapper in the glovebox. Phone dumps: deleted texts to an unknown Colorado number (October 8: “On way. Safe?”); Google queries like “untraceable phones” (October 5).

Ashlee’s silence stonewalls. Questioned thrice, she claims attorney privilege, offering only: “Melodee’s fine. This is a misunderstanding.” But her actions scream otherwise. She tore down missing posters in Lompoc, blocked family numbers, even skipped a vigil October 24. “It’s betrayal,” Corinna Meza, Melodee’s half-sister, says, her voice steel-edged in a Zoom interview. “Swapping plates to hide? What are you hiding, Ashlee? Our sister?”

Experts dissect the psyche. Dr. Rebecca Klein, a forensic psychologist at Stanford, profiles Ashlee as “narcissistic isolator,” driven by fear or fantasy. “Plate swaps suggest paranoia—fleeing perceived threats. But endangering a child? That’s pathological.” Theories abound: debt collectors (Ashlee dodged a repo man September); abusive ex (rumors of a 2023 restraining order, unsealed last week); or trafficking (FBI probes links to interstate rings). Online, Reddit’s r/FindMelodee swells with maps: “Hand-off in Durango?” “Hidden in Kansas barn?”

The hunt grinds on. Drones scan I-70; divers dredge reservoirs near Vernal, UT. Volunteers—500 from five states—comb trails, K-9s alerting to scents in a Grand Junction arroyo (false positive: deer carcass). Tips surge: 2,200 to 1-800-CALL-FBI, from a “wigged girl” in Omaha (debunked) to a Malibu wreck in Salina, KS (unrelated). A GoFundMe hits $25k; Truitt hires PIs for Nebraska sweeps.

Lompoc aches. Playgrounds echo empty; schools host assemblies on stranger danger. “Melodee’s our girl,” Mayor Jenelle Osborne said at a town hall. “We’ll bring her home.” Miranda clings to faith, lighting candles nightly: “She’s out there, unicorn in hand. God, guide her back.”

As snow dusts Colorado’s peaks, the swapped plates symbolize a deeper evasion—a mother dodging not just cams, but conscience. Melodee Buzzard, wherever you are, the nation’s eyes pierce the disguise. Tips to sbsoffice@sbsheriff.org. A family waits, hearts swapped for hope.