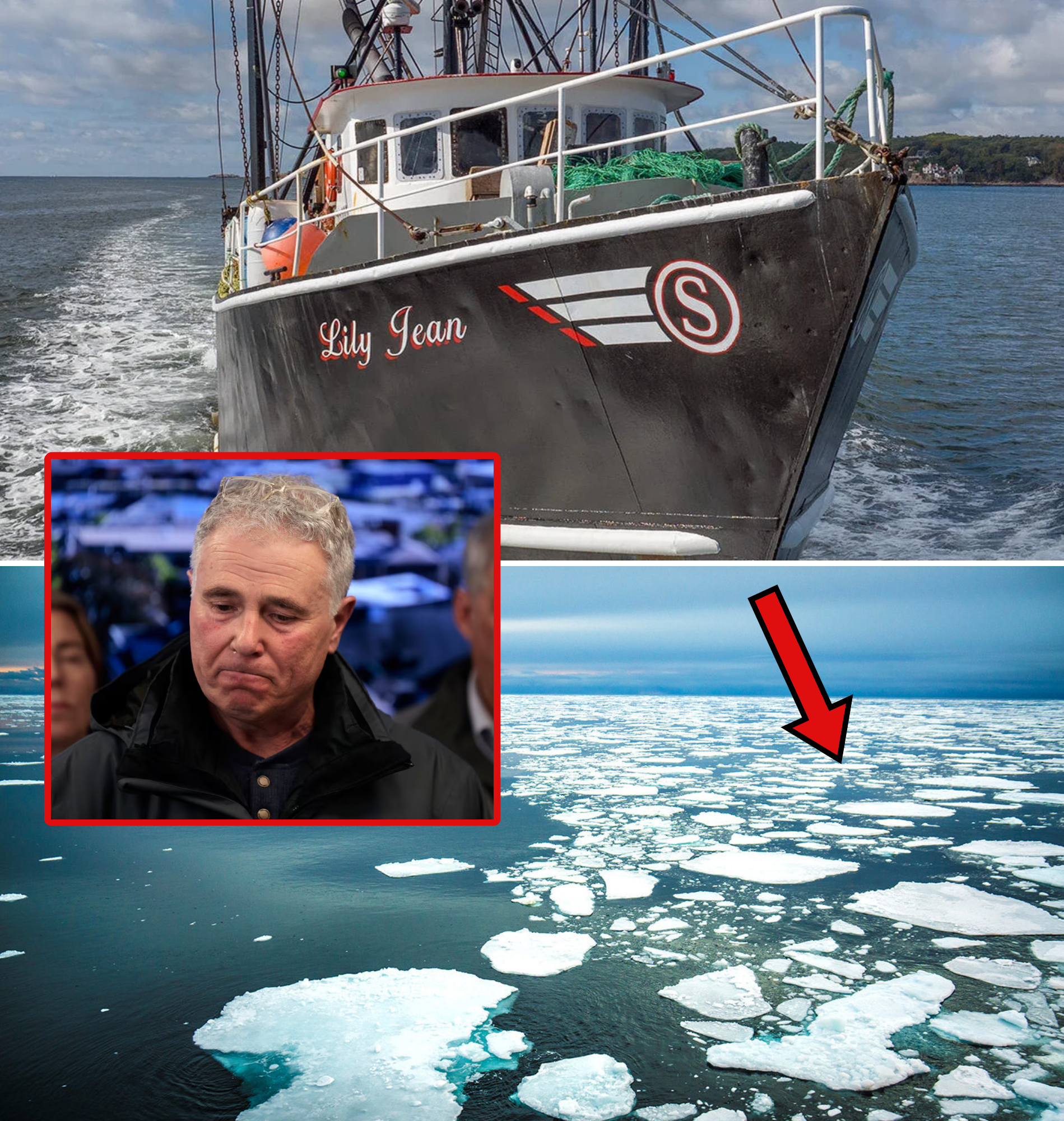

The rapid disappearance of the 72-foot fishing vessel Lily Jean on January 30, 2026, remains one of the most shocking maritime losses in recent New England history. All seven aboard—captain, crew, and a young NOAA observer—perished when the boat sank without warning, 25 miles off Cape Ann, Massachusetts. No distress call came over the radio. The only alert was the automatic EPIRB activation at 6:50 a.m., triggered as water flooded in during the capsize. Rescue arrived to debris, one body, and an empty life raft. The speed and silence pointed to a catastrophic stability failure, and emerging details from experts and analogous survivor testimonies confirm a single, deadly culprit: extreme ice buildup from freezing ocean spray.

Winter conditions that morning were merciless. Air temperatures hovered around 12°F, water at 39°F, with sustained winds of 24-30 knots whipping up 4-10 foot seas and heavy freezing spray. Under a National Weather Service heavy freezing spray warning, salt water droplets freeze almost instantly on contact with cold metal surfaces. On a fishing vessel like the Lily Jean—loaded with gear, possibly catch, and returning to port—the spray hits the rails, antennas, rigging, wheelhouse roof, and upper decks. Ice accretes asymmetrically and high up, sometimes adding thousands of pounds in hours. This weight aloft raises the vessel’s center of gravity far above the waterline, transforming a stable design into a top-heavy roller prone to capsizing at the slightest heel from a wave or shift.

The phenomenon is well-documented in commercial fishing safety reports. When ice accumulates unchecked, the boat becomes unstable; a sudden roll can exceed the righting moment, leading to downflooding through hatches or vents, then rapid sinking. Crews often have mere seconds to notice the list before the vessel flips. In the Lily Jean’s case, the absence of any manual distress signal aligns perfectly: the capsize was so abrupt that no one reached the radio or EPIRB manual trigger. The automatic beacon did its job, but by then, the boat was already inverting or flooding fatally.

A key insight comes from survivor accounts in similar incidents—though no one survived the Lily Jean, fishermen who endured near-misses describe the terror. One veteran from a comparable Gloucester grounding recalled ice forming so fast that “the boat felt like it was drunk—listing hard one way, then whipping over before you could grab an axe to chip it off.” In extreme cases, the weight forces open scuppers or shifts loose gear, exacerbating the free surface effect and momentum. For the Lily Jean, returning from a trip in these conditions, spray likely built up relentlessly on the upper structure. Without time or safe conditions to de-ice (using steam hoses, mallets, or hot water—methods that are risky in rough seas), the stability margin evaporated.

The Coast Guard and NTSB investigation, launched immediately, is examining stability calculations, load conditions, maintenance of de-icing equipment, and weather data. Early statements from officials noted ice buildup from freezing spray as a plausible factor that can cause capsize. No structural failure or collision evidence appeared in the debris field. The empty life raft suggests no opportunity to launch it; the crew may have been thrown into the water or trapped as the boat rolled.

This tragedy echoes historical precedents. The 1980s-90s saw multiple East Coast sinkings attributed to icing: vessels like the scalloper Harmony or dragger Northern Edge capsized after ice made them top-heavy in sub-zero gales. Safety campaigns since then emphasize de-icing protocols, but in practice, crews often push limits to protect gear or reach port. The Lily Jean’s appearance on “Nor’Easter Men” highlighted the grit of Gloucester fishermen facing such risks daily.

Beyond the immediate cause, broader implications emerge. Enhanced stability awareness training, mandatory real-time inclinometers, and automated de-icing systems could mitigate future risks. EPIRBs saved the alert, but personal locator beacons (PLBs) on each crew member might have aided location in the chaos. Immersion suits, if worn, extend survival in cold water, though the speed here likely rendered them moot.

Gloucester mourns deeply. Captain Accursio “Gus” Sanfilippo, a fifth-generation fisherman known for skill and spirit; father-son team Paul Beals Sr. and Jr.; John Rousanidis, Freeman Short, Sean Therrien; and 22-year-old Jada Samitt, whose NOAA role embodied dedication to sustainable seas. Memorials at the fishermen’s statue and harbor lights honor them, reminding all of the ocean’s unforgiving nature.

As the probe continues—likely months-long—the story of the Lily Jean underscores a harsh truth: in the dead of winter, ice isn’t just discomfort—it’s a silent killer that can steal a vessel and its crew in heartbeats. Preventing the next loss demands vigilance, technology, and respect for conditions that turn the sea lethal.