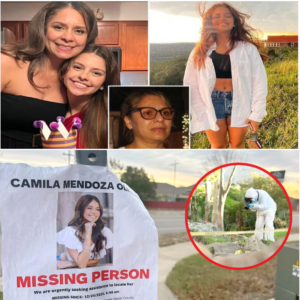

In the shadowed canyons of Arizona’s White Mountain Apache Reservation, where the ponderosa pines stand as ancient guardians against the relentless desert sun and the wind carries echoes of ancestral songs through the canyons, the disappearance of 16-year-old Challistia “Tia” Colelay unfolded like a nightmare scripted in silence. Reported missing on October 27, 2025, after vanishing from her home in Whiteriver—a tight-knit community of 4,000 souls nestled on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation—Tia’s story gripped the hearts of her family, tribe, and a nation already weary of tragedies that claim Indigenous lives with quiet ferocity. For seven harrowing days, search parties combed the rugged terrain, volunteers from the Navajo Nation and Hopi communities fanning out with flashlights and flyers, their calls of “Tia! Tia!” swallowed by the vastness of the landscape. Then, on November 3, in a clearing less than a mile from her family’s modest home, the unthinkable: Tia’s remains were discovered, her young body hidden amid the underbrush, the cause of death ruled a homicide by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Police, in a statement that landed like a thunderclap, confirmed the teen had been murdered, though details remain shrouded in the fog of an ongoing investigation. “This goes on far too often,” lamented Darlene Gomez, an attorney and activist with the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Relatives (MMIWR) coalition, her voice a raw edge of frustration during a press briefing outside the White Mountain Apache Tribal headquarters. “Tia wasn’t just a runaway—she was a daughter, a sister, a dreamer. And the system failed her, like it fails so many of our girls.” As the Fort Apache community wraps itself in grief—red ribbons fluttering from porches, prayer vigils lighting the night under a canopy of stars—Tia’s death has reignited a national cry for justice, exposing the gaping wounds of the MMIWR crisis that claims thousands of Indigenous lives each year, often vanishing into jurisdictional voids and underfunded responses.

Tia’s life, though brief, burned with the quiet fire of a girl on the cusp of everything. Born on April 12, 2009, in the heart of Whiteriver to parents deeply rooted in Apache traditions—her father, a silversmith crafting intricate jewelry inspired by ancestral motifs, and her mother, a community health worker advocating for diabetes prevention in a tribe plagued by health disparities—Tia was the third of 12 siblings in a household that blended the old ways with the relentless pull of modernity. Growing up in a modest adobe home on the reservation’s edge, where the mornings echoed with the call of mourning doves and evenings brought family circles around a crackling fire pit, Tia embodied the resilience of her people. At Alchesay High School, she was a standout in the art club, her sketchbooks filled with vivid portraits of eagles soaring over the White Mountains and dreamcatchers woven from river reeds. “Tia had this laugh—like wind chimes in a breeze,” her older sister, who identified herself only as “Lila” in a tearful GoFundMe post, wrote amid pleas for funeral donations. “She was the goofy one, always pulling pranks with her little brothers, braiding wildflowers into her hair for school dances. She dreamed of being a graphic designer, creating logos for tribal businesses—something that honored where we come from.” Classmates remember her as the girl who’d organize impromptu basketball games on the reservation courts, her quick feet and quicker wit making her a favorite, or the one slipping notes of encouragement into lockers during finals week. “She saw the good in everyone, even when life kicked hard,” her art teacher, Ms. Elena Tsosie, shared at a candlelit vigil on November 5, where 300 gathered under a harvest moon, their faces illuminated by flames flickering in mason jars. Tia’s heritage ran deep: a descendant of the White Mountain Apache scouts who once guided U.S. troops through these canyons, she participated in traditional ceremonies, her small hands grinding corn for ceremonial bread and her voice joining the chorus in sunrise prayers at the tribe’s sacred sites.

Yet, beneath the surface of Tia’s vibrant world, shadows loomed—cracks in the reservation’s resilient facade that mirrored the broader struggles of Indigenous youth. Whiteriver, with its 90% poverty rate and unemployment hovering at 50%, grapples with the intergenerational trauma of boarding schools and land loss, where substance abuse and domestic violence cast long pall. Tia’s family, like many, navigated these tides: her father’s silversmithing a sporadic income supplemented by tribal stipends, her mother’s health work a beacon amid the diabetes epidemic claiming one in three Apache adults. Reports of Tia’s earlier disappearances—twice in the past year, each time chalked up to “runaway” status—now haunt investigators, a pattern that advocates like Gomez decry as deadly dismissal. “Indigenous girls aren’t ‘runaways’—they’re fleeing something,” Gomez said, her words a scalpel in a November 6 CNN interview, where she cited the FBI’s 2023 data: 5,712 MMIWR cases nationwide, with only 400 cleared, and Arizona’s reservations a hotspot where jurisdictional tangles between tribal, state, and federal agencies delay responses by weeks. Tia’s last sighting, on October 16, came during a casual visit to a friend’s home in nearby Cibecue—a sleepover planned for stargazing and s’mores that stretched into days of unanswered texts. “She said she was heading to a friend’s, something about girl talk,” Lila recounted in the GoFundMe, which has raised $45,000 for funeral costs and sibling counseling. “We didn’t worry at first—kids do that. But when the calls stopped, the fear set in.” By October 27, with no school attendance and friends reporting “Tia hasn’t been around,” the White Mountain Apache Police Department logged the missing person report, dispatching patrols along the reservation’s winding roads but hampered by understaffing—only 12 officers for 1.6 million acres—and spotty cell coverage that swallowed tips.

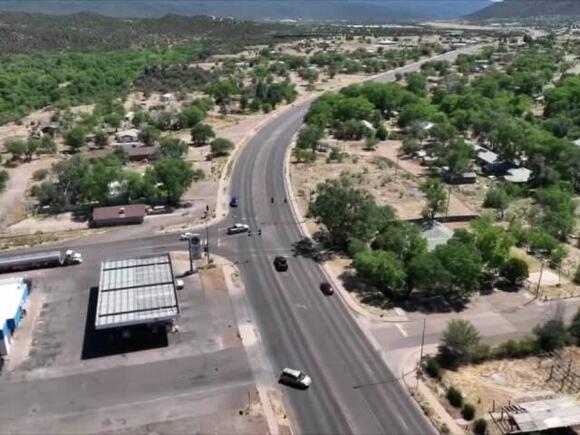

The search, a desperate mosaic of man-hours and community calls, mobilized the tribe’s spirit of solidarity. Volunteers from the Fort Apache Volunteer Fire Department and the Navajo County Search and Rescue fanned out from Whiteriver, combing arroyos and abandoned hogans with ATVs and bloodhounds, their flashlights piercing the October chill. Social media amplified the plea: #FindTia trended on TikTok with 1.2 million views, teens recreating her photo in red filters symbolizing missing Indigenous women, while the tribe’s Facebook page exploded with 5,000 shares of her image—braids framing a shy smile, eyes sparkling with unspoken stories. Flyers fluttered from telephone poles in Pinetop-Lakeside, 30 miles south, and prayer circles at the tribe’s Community Center invoked the Apache crown dancers’ blessings for safe return. “We searched every draw, every dry wash,” said Tribal Police Chief Ramon Rios in a November 4 briefing, his face lined with exhaustion. “Tia was one of ours—a good kid, full of light. When we found her…” His voice trailed, the weight of “remains” unspoken but understood. On November 3, a routine patrol along Bushmaster Drive—a rutted access road flanking Highway 180, dotted with abandoned vehicles and tumbleweeds—led to the clearing: a shallow depression in the scrub, hastily covered with branches and debris, where cadaver dogs alerted to human scent. Officers unearthed Tia’s body, clad in the same jeans and hoodie from her last sighting, her remains in an advanced state of decomposition that suggested days exposed to the elements. “It was like the land tried to hide her, but couldn’t,” one responder confided to a local reporter, voice hushed. The cause of death, pending full autopsy from the Navajo County Medical Examiner’s Office, points to homicide—blunt force trauma and possible asphyxiation, per preliminary reports—though details remain sealed to protect the investigation.

The discovery’s horror rippled through Whiteriver like a shockwave, a community already scarred by the MMIWR epidemic now convulsing in collective grief. Vigils sprang up overnight: November 4 at the tribe’s gymnasium, 400 gathered under fluorescent lights, elders leading songs in Western Apache while youth held signs reading “No More Stolen Sisters.” Lila’s GoFundMe post, raw with rage and remembrance, went viral: “Tia was our goofy girl, the one who’d sneak extra frybread at feasts, braid wildflowers into crowns for her little brothers. She dreamed of art school in Phoenix, designing clothes that told our stories. Now she’s gone, and the police say murdered. Who? Why? Our hearts are shattered—who will bring her justice?” Donations poured in from across the Southwest: $10 from a Flagstaff barista who’d taught Tia pottery, $500 from a Phoenix MMIWR nonprofit. Gomez, whose organization has litigated 50 cases since 2019, arrived by November 5, her press conference outside the tribal council chambers a clarion call: “Tia’s not the first, won’t be the last if we don’t act. Runaway labels bury our girls—underfunding, undertraining, jurisdictional limbo. Arizona’s reservations are ground zero for MMIWR, with 2,000 cases unsolved since 2010. Tia’s blood cries for change—mandatory Turquoise Alerts for Indigenous youth, federal task forces, real resources.” The Turquoise Alert, Arizona’s answer to Amber, was notably absent in Tia’s case—no request from tribal police, per DPS, but advocates blast the gap: only 15% of reservation cases qualify, versus 70% urban.

Tia’s family, a sprawling web of aunts, uncles, and cousins bound by Apache kinship, reels in the aftermath. Her father, a quiet craftsman whose silver conchos grace tribal powwows, has retreated to his workshop, hammers falling silent as he carves a memorial pendant etched with Tia’s initials. “She was my shadow—following me to the forge, asking about every stamp,” he told a local reporter through tears, his hands still smelling of solder. Lila, 22 and a mother herself, channels fury into action: organizing youth safety workshops at the community center, where girls learn self-defense and emergency codes. “Tia texted me the night she left—’Sis, things feel off.’ I should’ve pushed harder,” she confesses in a November 7 interview, her voice steeling. The brothers, 12 and 10, huddle in counseling at the tribe’s behavioral health clinic, their drawings of “Tia flying with eagles” a fragile bridge to healing. Community leaders, from Tribal Chairman Dallas Massey Sr. to Councilwoman Claudia Thompson, vow reform: a $2 million grant proposal for tribal police tech—drones, better radios—and partnerships with the FBI’s MMIWR unit. “Tia’s spirit walks with us,” Massey said at a November 9 council meeting, 150 packed into the chamber. “She demands we listen louder, act swifter.”

As November’s frost tips the sage, Whiteriver heals in halves: a GoFundMe-funded funeral on November 15, her casket draped in Apache baskets, songs rising like smoke from the graveside fire. The investigation churns—tips flooding the hotline, BIA agents canvassing Whiteriver’s 200 homes—but answers lag, the suspect unknown, the why a wound. Tia’s sketchbook, recovered from her room, holds horses galloping free—her unspoken escape. In Arizona’s arid ache, Challistia Colelay’s cry echoes: a girl gone, a crisis unhealed, a call for justice that refuses to fade. “This goes on far too often,” Gomez repeats, her words a vow. For Tia, the wind carries her forward—a whisper in the pines, demanding dawn.