In the crisp autumn air of New Britain, Connecticut, where maple leaves carpet sidewalks like forgotten warnings, a community’s grief has ignited a firestorm of reform. Just weeks after the horrific discovery of 11-year-old Jacqueline “Mimi” Torres-Garcia’s remains in a plastic storage bin behind an abandoned Clark Street home on October 8, 2025, an online petition dubbed “Mimi’s Law” has exploded onto the scene. Launched by New Haven resident and father of an 11-year-old, Los Fidel, the Change.org drive has amassed nearly 14,000 signatures in a mere five days as of November 10. What began as a father’s anguished response to a story that “broke my heart” has snowballed into a clarion call for sweeping changes to child welfare laws, spotlighting the lethal gaps in oversight for homeschooled children, fractured families, and overburdened agencies. As lawmakers brace for a legislative session heavy with accountability demands, Mimi’s Law isn’t just a petition—it’s a reckoning, a vow that no other child will vanish into the shadows of neglect.

Mimi’s story, unearthed layer by agonizing layer through unsealed arrest warrants and police interviews, is a tapestry of betrayal woven from the threads of everyday dysfunction. Born in 2014 to Karla Roselee Garcia, 29, and Victor Torres, Mimi navigated a childhood marked by custody tug-of-wars and whispers of instability. Torres, her devoted father, shared joint guardianship reinstated in May 2022 after stints with her paternal grandmother, who had cared for Mimi and her younger sister amid Garcia’s early parental lapses. By 2023, Garcia had entangled herself in a volatile relationship with Jonatan Nanita, 30, a man shadowed by prior convictions for theft and assault. The family, scraping by in low-rent apartments across New Britain and Farmington, withdrew Mimi from public school on August 26, 2024—her would-be first day of sixth grade—citing a move to Farmington and intent to homeschool. What followed was not education, but erasure.

Investigators believe Mimi perished in September 2024, her tiny frame—already ravaged by months of deliberate starvation—weighing just 26 to 27 pounds, a skeletal whisper of the vibrant girl who once skipped through courtyards sketching unicorns. The Chief Medical Examiner’s report, released on November 7, ruled her death a homicide by fatal child abuse through chronic malnutrition. No drugs, no fatal blows—just the insidious erosion of hunger as a tool of control. Warrants detail Garcia’s confession: an argument over her pregnancy escalated, with Mimi allegedly shoving her mother down stairs, prompting Nanita’s rage-fueled kick to the head. Garcia later admitted to zip-tying her daughter’s limbs, confining her to a bedroom, and doling out scraps while the household carried on. Nanita, discovering the unresponsive child, panicked and stashed her in a basement tote doused with ammonia to stifle the stench. For months, the bin lurked like a family heirloom, trailing them through evictions and hotel stays until Garcia enlisted Nanita for disposal in early October 2025. Her sister, Jackelyn Garcia, 28—previously convicted of risk of injury to a minor—allegedly aided the concealment, facing her own litany of charges.

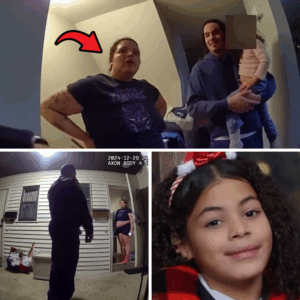

The deception ran deeper still. As the body decayed below, Garcia allegedly duped the Department of Children and Families (DCF) during a welfare check tied to bruises on Mimi’s younger sibling. In early 2025, Garcia claimed Mimi was homeschooling out-of-state and arranged a video call where another child, coached to impersonate her, assuaged caseworkers’ concerns. “This information has been provided to law enforcement,” DCF Interim Commissioner Susan Hamilton stated, her words a damning admission of vulnerability. Neighbors in Farmington, haunted by four noise complaints from September 2024 to February 2025—screams, thuds, pleas of “stop”—recalled eerie bodycam footage from a December 29 visit. Officers chatted amiably with Garcia and Nanita at the door, oblivious to the crypt below. When asked about children, only Nanita’s toddler son surfaced; Mimi, officially “homeschooled,” evaporated from the narrative.

This veil of normalcy, pierced only when Nanita’s acquaintances stumbled on the bin and dialed 911, has fueled the petition’s fury. Los Fidel, a Bridgeport advocate shaken by the tale, launched “Demand Accountability and Create ‘Mimi’s Law'” on October 18, framing it as a bulwark against “children slipping through the cracks.” By November 10, signatures topped 13,900, with signers from across Connecticut and beyond pouring out stories of their own brushes with the system. “As a former foster kid, DCF did more harm than good,” one wrote. “They snatch from safe homes and leave kids in hell.” Another, a homeschool alum, decried the “lax oversight” that nearly swallowed her youth. Fidel, collaborating with Mimi’s family—including a devastated Torres, who laments ignored custody pleas—has pitched the proposal to Governor Ned Lamont and state legislators, eyeing the 2026 session.

At its core, Mimi’s Law targets four pillars of reform, each a direct rebuke to the failures that doomed Mimi. First: mandatory periodic in-person welfare checks for all homeschooled children, conducted by neutral parties like the Department of Education, DCF, or pediatricians. Connecticut’s homeschool laws, per a recent Office of Legislative Research report, lean on voluntary guidelines rather than statutes—looser than neighbors like New York (annual assessments) or Massachusetts (quarterly progress reports). Over 5,100 kids withdrew from public schools in the past three years, nearly a quarter from DCF-involved families, vanishing into unregulated voids. Second: DCF accountability mandates, including body cameras for caseworkers to document visits and an independent oversight board to probe dropped balls. Hamilton’s agency, down to 2,800 staff from 3,000 pre-pandemic, grapples with turnover and caseloads that dilute diligence.

Third: bolstering non-custodial parents’ rights, ensuring no guardian can sever access entirely—a nod to Torres’s thwarted visits and Garcia’s alleged isolation tactics. Fourth: a blanket prohibition on convicted child abusers residing with minors, spotlighting Jackelyn Garcia’s parole into the home post-conviction. “Mimi was erased in silence,” Fidel writes. “Her death must mean something.” A companion petition by Vernon realtor and mother Brenda Milhomme, “Mimi’s Law: Child Protection Reform in Connecticut,” echoes these calls, nearing 200 signatures and urging annual well-being checks via school districts or doctors. Together, they’ve sparked a chorus: over 14,000 voices demanding that homeschooling’s freedoms not eclipse safety nets.

The groundswell resonates in Hartford’s halls. State Senator Saud Anwar (D-Norwalk), co-chair of the Children’s Committee, anticipates bills mirroring the petition, including enhanced identity verification for DCF interviews—perhaps biometrics or in-person confirmations—to foil video charades. “We’re assessing resources and probing policy tweaks,” he said, echoing calls for more social workers amid national shortages. Representative Mary Beth Tingling (D-Stamford) decries the “public health crisis” of unchecked abuse, linking it to rising youth anxiety and depression. Homeschool advocates, via the Coalition for Responsible Home Education, counter that Mimi died pre-withdrawal (court records peg an offense date of June 21, 2024), urging targeted interventions over blanket burdens. “Balance parental rights with child welfare,” urges CRL executive director Rachel Coleman. Yet, the petition’s momentum drowns dissent; Fidel’s outreach to media—FOX61, WFSB, CT Mirror—has amplified it statewide.

Victor’s Torres’s voice cuts sharpest. From his New Britain home, surrounded by Mimi’s drawings and stuffed animals, he channels rage into resolve. “I fought for her every day, but the system shut me out,” he told reporters post-arraignment on October 14, where Garcia, Nanita, and Jackelyn Garcia shuffled in orange, bonds at $10 million apiece. Torres, backed by grandparents petitioning to raze the Clark Street eyesore for a memorial park, embodies the human toll. “Mimi loved to dance, to laugh—she deserved the world, not a box.” His younger daughter, now in his care, attends school under vigilant eyes, a microcosm of the reforms sought. Community vigils, from candlelit walks to teddy-bear memorials on Clark Street, swell with supporters: parents, educators, survivors. “Justice for Little Mimi,” they chant, signs reading “No More Invisible Children.”

As November’s chill deepens, Mimi’s Law teeters on the cusp of transformation. With signatures surging—Change.org alerts lawmakers every 25 new ones—the petition pressures the General Assembly to act. Fidel envisions a legacy: annual check-ins as routine as flu shots, body cams as standard as badges, co-parenting portals to bridge divides. Critics fret overreach, but proponents counter: in a state where two heart-wrenching cases last year—a Waterbury teen held captive two decades, Mimi’s bin-bound fate—exposed the peril of the unseen, the cost of inaction dwarfs any inconvenience. DCF’s Hamilton, reviewing the family’s file (interactions from 2014-2021, none post-2022), pledges internal audits, but external eyes demand more.

Mimi Torres-Garcia wasn’t just a victim; she was a spark—a gap-toothed dreamer whose absence exposes the fragility of safeguards. Her story, from playground giggles to forensic tragedy, mirrors national woes: 1.7 million U.S. homeschooled kids in 2023, per Census data, many in low-oversight states like Connecticut. As petitions proliferate—another by Cath Joyce seeks DOE-mandated annual reviews—the dialogue evolves from mourning to mandate. Will Lamont sign? Will bills pass by February’s session end? On November 10, with 13,950 signatures and climbing, the answer brews in public fury. Mimi’s Law isn’t legislation yet—it’s a movement, a mother’s withheld embrace turned into a father’s fierce advocacy, a child’s silence shattered by thousands. In New Britain’s quiet streets, where porch lights flicker against encroaching dusk, one truth endures: Jacqueline “Mimi” Torres-Garcia will not be forgotten. Her name, now etched in digital ink, demands a future where no bin hides a horror, no video veils a void. For Mimi—and the children yet unseen—Connecticut must listen, legislate, and protect.