On a balmy summer afternoon in January 1970, Fairy Meadow Beach in Wollongong, New South Wales, buzzed with the carefree energy of families escaping the Australian heat. Waves crashed gently against the shore, children squealed in the surf, and the salty air carried the scent of sunscreen and barbecues. For the Grimmer family—recent arrivals from the gray skies of Bristol, England—this was meant to be a perfect day of new beginnings. They had emigrated as “Ten Pound Poms,” lured by the promise of sun-soaked opportunities in a land of endless summers. But within moments, their dream shattered into a nightmare that would haunt Australia for generations.

Three-year-old Cheryl Grimmer, with her cherubic face and blonde curls, was the youngest of four siblings. She had been splashing in the shallows with her brothers when her mother, Carole, decided it was time for showers. The family trudged to the weathered concrete changing rooms, a simple block overlooking the dunes. Carole turned her back for just a minute—long enough to wring out towels and gather towels. When she looked up, Cheryl was gone. “Cheryl? Cheryl!” The call echoed unanswered. Witnesses later recalled seeing a small figure in a red swimsuit scampering toward the showers, but no one saw her after that. In an instant, the vibrant beach fell silent under the weight of panic.

What followed was a frenzy that gripped the nation. Police swarmed the sands, combing dunes, scrubland, and nearby creeks with dogs and divers. Helicopters thumped overhead, and media helicopters captured the chaos for nightly news bulletins. Volunteers—hundreds of them—sifted through long grass and bushland, their faces etched with determination and dread. The story of the missing British toddler exploded across Australian headlines, a stark reminder of vulnerability in paradise. “Little Cheryl: Australia’s Lost Angel,” one tabloid proclaimed, plastering her school photo on front pages. For weeks, the public held its breath, but no trace emerged. Cheryl’s body was never found, and the case slipped into the shadows of unsolved mysteries, leaving a scar on the collective psyche.

The Grimmers, already adrift in a foreign land, were thrust into an abyss of grief. Father Norman, a factory worker, and mother Carole had packed up their lives in 1969, chasing the Australian dream with £10 each—a government scheme that symbolized post-war migration hopes. Their boys—John, Paul, and Rick—were old enough to adapt, but Cheryl, barely out of diapers, represented innocence unmarred by the world’s cruelties. The family clung to each other in their modest Wollongong home, fielding endless questions from detectives and reporters. “We came here for a better life,” Carole would later say in interviews, her voice cracking. “Instead, we lost everything.” The boys grew up under the cloud of that day, each carrying a piece of the trauma. Rick, just nine at the time, remembered lifting his sister for a sip from the outdoor water fountain moments before she vanished—a detail that would prove hauntingly pivotal decades later.

As the years dragged on, the investigation faltered. Early leads fizzled: a sighting of a man with a child near the beach, whispers of a suspicious vehicle, even rumors of a pedophile ring in the area. But without physical evidence, the trail went cold. Australia, a young nation still defining its identity, was no stranger to child abductions—cases like the Beaumont children in 1966 had already seared similar wounds—but Cheryl’s story resonated deeply. It exposed the fragility of coastal idylls, where families sought solace only to find horror. Public fascination simmered through true crime books, documentaries, and playground whispers. The Grimmers became reluctant symbols of endurance, attending memorials and lobbying politicians, their pleas for answers echoing in empty chambers.

By the 1980s, hope dimmed. Norman passed away in 2001, never knowing peace. Carole soldiered on, but the family’s fracture was irreparable. The boys scattered: John to quiet obscurity, Paul to a life shadowed by activism, Rick to the role of reluctant archivist, poring over yellowed clippings. Yet, in 2011, a coroner’s inquest breathed faint life into the embers. Magistrate Sharon Freund declared Cheryl legally dead, citing overwhelming evidence of foul play. “She was abducted and murdered,” the report stated bluntly, urging police to reopen the file. It was a validation, however grim, that spurred the New South Wales Homicide Squad into action. Detectives dusted off archives, re-interviewed witnesses, and pored over forensic possibilities in an era of advancing DNA tech. But the beach’s sands had long swallowed secrets, and progress was glacial.

Then, in a dusty corner of police records, came the bombshell: a forgotten transcript from 1971. Less than 18 months after Cheryl’s disappearance, a troubled 17-year-old boy—let’s call him “Mercury” for the purposes of this retelling, as legal shadows still cloak his name outside privileged walls—sat in a stark interview room at Sydney’s Metropolitan Children’s Shelter. He was a local lad, 15 at the time of the crime, with a history of instability: runaway episodes, a fractured home, and an intellect hampered by circumstance. No parent or lawyer flanked him—a glaring oversight in today’s standards, but routine then. Under questioning, he cracked.

The confession was chilling in its specificity. Mercury described approaching the showers, spotting the little girl in red, and luring her away with a promise of play. He recounted carrying her to the dunes, her small hands trusting in his. There, in the scrub, he admitted to binding her wrists with a makeshift cord, silencing her cries, and committing unspeakable acts driven by a adolescent’s warped curiosity. He spoke of destroying her swimsuit, covering her tiny body with leaves and branches, and fleeing as dusk fell. Most damning: he mentioned lifting her to the water fountain for a drink—a private family moment no stranger could know. “I just wanted to see what it was like,” he allegedly said, his words a grotesque echo of innocence twisted. Detectives, stunned, filed the statement, but without a body or corroboration, it gathered dust. The boy was counseled, not charged, and the case meandered on.

For years, this phantom document slumbered, a ghost in the machine of bureaucracy. Mercury rebuilt a life in Wollongong’s quiet suburbs, blending into the community as a tradesman, husband, father—his past a sealed vault. Neighbors knew him as unassuming, perhaps reclusive, but harmless. The Grimmers, oblivious to the lead, raged against institutional indifference. Paul, now in his 50s, channeled fury into advocacy, co-authoring reports on police missteps: delayed searches, overlooked tips, a failure to canvas the beach’s transient crowds. “They treated us like nuisances,” he recalled. In 2022, a BBC podcast, “Fairy Meadow,” hosted by journalist Jon Kay, reignited interest. It unearthed three potential witnesses—beachgoers from 1970—who corroborated vague sightings of a youth with a child. Cadaver dogs sniffed “areas of interest” in the dunes, unearthing bones that proved animal, not human. The family, undeterred, funded private probes, their savings drained by a quest that felt Sisyphean.

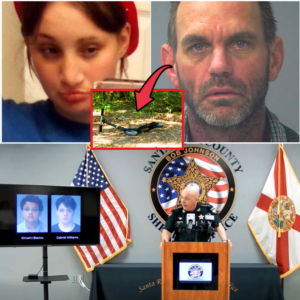

By 2016, renewed vigor from the coroner’s nudge led to a breakthrough. Homicide cold-case experts, armed with the 1971 transcript, built a case around it. In March 2017, Mercury—now in his 60s, graying and weathered—was arrested at dawn, handcuffs clicking in the home he shared with his wife. Charged with abduction and murder, he pleaded not guilty, his face a mask of bewilderment. The trial loomed like a storm cloud over Wollongong, dredging up old wounds. Courtrooms buzzed with spectators, many who remembered the beach siege as if it were yesterday. But justice, elusive as ever, slipped away.

In 2019, the Supreme Court of New South Wales delivered a crushing blow. Justice Robert Allan Hulme, scrutinizing the confession’s origins, deemed it inadmissible. The interview, he ruled, violated modern notions of fairness. The boy—immature, low-IQ, isolated—had been coerced, psychiatrists testified, his vulnerability exploited in a room devoid of safeguards. No video, no Miranda rights equivalent; just a teenager unraveling under pressure. Without this cornerstone, the prosecution crumbled. The director of public prosecutions conceded: insufficient evidence. Mercury walked free after nearly a year in custody, his identity suppressed under child protection laws—the Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987 shielding juvenile offenders from lifelong stigma. The confession was sealed, a forbidden fruit. “It’s like they murdered her twice,” Paul Grimmer fumed to reporters outside court, tears streaming. The family, bankrupted emotionally and financially, vowed to fight on.

The 2020s brought a slow burn of momentum. The podcast’s ripples drew parliamentary eyes to cold cases, highlighting systemic flaws: underfunded squads, evidentiary loopholes, the torment of families left dangling. Cheryl’s story became a rallying cry, emblematic of dozens of “long-term missings” in Australia—children vanished into the outback or urban sprawl, their echoes fading. In October 2025, as the 55th anniversary approached, the Grimmers issued a desperate ultimatum. Through allies, they contacted Mercury: meet by midnight, explain your knowledge of that fountain detail, declare your innocence or guilt. Silence. No response from the man who’d once poured out his soul to detectives.

Enter Jeremy Buckingham, a maverick MP from the Legalise Cannabis Party, whose conscience was pricked by the podcast and family pleas. On October 23, 2025, in the hallowed chamber of the New South Wales Legislative Council, he invoked parliamentary privilege—a rare parliamentary superpower shielding lawmakers from libel suits or contempt charges. Under its cloak, Buckingham rose, voice steady at first, and named Mercury fully. Gasps rippled through the gallery, where Paul and Linda Grimmer sat stone-faced. Then, haltingly, choking back sobs, he read the confession aloud: the dunes, the binding, the leaves, the fountain. “This is a known murderer walking free,” Buckingham thundered, his motion calling for a sweeping inquiry into unsolved abductions. Cross-party support coalesced; the government, days earlier, had upped the reward to $1 million—a fortune for the tip that cracks it.

The chamber erupted in debate. Legislative Council President Ben Franklin interjected, warning of privilege’s “responsible use” and potential backlash for breaching suppressions. Attorney General Michael Daley, voice heavy, acknowledged the “heartbreak” but treaded carefully: “Parliamentary processes are independent; I won’t comment on uncharged individuals.” Outside, media swarmed, but legal chains held—the Act forbade naming Mercury in print or broadcast, fining violators up to $110,000 or jailing them. Yet the genie was out: whispers spread online, neighbors connected dots, and the public roared back to life. #JusticeForCheryl trended, with Wollongong locals sharing faded photos and armchair sleuths debating the fountain clue.

For the Grimmers, it was catharsis laced with caution. Gathered post-session, Linda—Paul’s wife, the family’s steadfast anchor—read their statement to a crush of microphones. Paul, overcome, handed it off mid-sentence, his shoulders shaking. “What we want now is the truth,” she said firmly. “We’re not here to harm him or his family. We just want him questioned in court, under oath, so witnesses can come forward.” They spoke of five decades’ toll: sleepless nights, fractured bonds, the ghost at every holiday table. “Cheryl would be 58 now,” Paul added later, in a rare aside. “A grandmother, maybe. Instead, she’s frozen at three.” The family hoped the disclosure would jolt memories loose—perhaps a bushwalker from 1970, a relative with secrets. NSW Police, defensive yet diligent, affirmed the case’s openness: homicide detectives on alert, the million-dollar carrot dangling.

Broader ripples lap at Australia’s justice shores. Buckingham’s motion birthed an inquiry into long-term missing persons, probing investigative lapses and tech upgrades like genetic genealogy. Cases like the Beaumonts or Mr. Cruel may benefit, exposing how 1970s policing—reliant on paper trails and gut instinct—faltered against modern scrutiny. Critics decry the privilege ploy as vigilante theater, risking miscarriages if Mercury’s innocence holds. He, through lawyers, maintains denial, his life upended anew by spotlights he evaded for decades. Subpoenas loom; the inquiry could summon him, piercing the veil once more.

As autumn sunsets paint Fairy Meadow gold, volunteers return to the dunes, detectors humming. The Grimmers, weathered but unbowed, plant a memorial plaque: “Cheryl Grimmer, Beloved Sister, Forever Three.” Fifty-five years on, the case teeters on resolution’s brink—not solved, but cracked open. Will Mercury face a dock? Will bones surface from the scrub? Or will the tide claim another secret? For now, Australia’s gripped anew, whispering: justice delayed, but perhaps not denied. In the waves’ roar, a little girl’s laughter lingers, demanding to be heard.