The Red Red Wine Club on Music Row was alive with the low hum of Nashville’s elite—songwriters nursing whiskeys, publishers trading war stories, and a smattering of stars in tailored denim, all gathered under the chandeliers for the 72nd annual BMI Country Awards on November 19, 2024. The air crackled with the afterglow of accolades: Morgan Wallen’s “Last Night” crowned Song of the Year, Zach Bryan and Chase McGill tying for Songwriter of the Year with six chart-toppers apiece, and Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Corp. claiming Publisher honors for helming 34 of the night’s 50 most-performed tunes. But as the evening crested toward its emotional zenith, Blake Shelton and Luke Bryan took the stage and transformed the ceremony into something sacred—a tear-filled tribute to Alabama frontman Randy Owen that stopped the room dead in its tracks. Their raucous rendition of “Mountain Music,” Owen’s 1982 anthem of Appalachian joy and grit, didn’t just echo off the walls; it bound the crowd in a collective chorus, turning strangers into a family choir and leaving the country legend, a BMI Icon for 2024, overwhelmed in the front row, dabbing at his eyes with a handkerchief that had seen better nights.

Blake Shelton, the lanky Oklahoma drawler who’s spent two decades turning barroom confessions into arena anthems, kicked it off solo, his voice a warm rumble over a lone guitar riff that evoked lazy rivers and lightning bugs. “There’s a lot ’bout livin’ you gotta learn as you go,” he crooned, his Stetson tipped low, the lyrics landing like old friends at a reunion. The room, packed with 800 industry faithful in black-tie twang, leaned in, sensing the shift from celebration to consecration. Then, mid-verse, the lights dipped, and out bounded Luke Bryan—Georgian firebrand with a grin wide as the Chattahoochee—striding onstage unannounced, mic in hand, his energy a spark to Shelton’s steady flame. “Oh, there’s a lot about lovin’ you’ll never know,” Bryan joined, his tenor soaring in harmony, the duo trading lines like brothers swapping fishing lies. Backed by a searing fiddle that wailed like a homesick train whistle, they ramped it up: Shelton stomping the beat, Bryan clapping the rhythm, the crowd surging to its feet in a wave of whoops and swaying shoulders. By the chorus—”Mountain music is you and me”—the entire hall was singing, voices blending from soprano sighs to bass bellows, a spontaneous hymn that drowned out the AC hum and turned the venue into a back-porch hoedown.

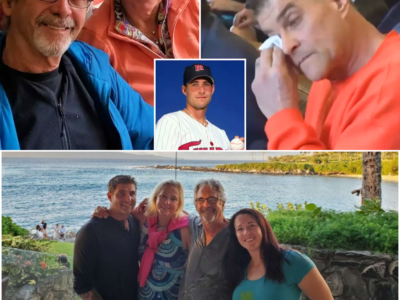

Owen, seated front and center in a crisp white shirt that couldn’t hide the tremor in his hands, watched it all unfold with the quiet awe of a man who’s seen 75 million albums sold but never quite believed it. At 74, the Fort Payne farm boy who’d traded cotton fields for chart-topping gold looked every bit the elder statesman, his salt-and-pepper beard framing a face etched with the lines of a lifetime in the spotlight. As the final notes faded—Shelton and Bryan locking arms, sweat-slicked and beaming—Owen rose, applause crashing like thunder, and pulled them into a bear hug that spoke volumes no speech could. “Y’all just took me home,” he rasped into the mic, voice cracking as fresh tears welled. “That’s what this music does—it brings us back to where we started, together.” The room, still buzzing from the unity, erupted again, but it was the hush that followed, the shared sniffles and knowing nods, that sealed the magic. It wasn’t theater; it was transfusion, a raw infusion of gratitude from two modern titans to the pioneer who’d paved their path.

To grasp the gravity of that embrace, you have to rewind to Owen’s origins—a tale as rooted in red dirt as a pecan tree. Born Randy Yeuell Owen on December 13, 1949, in a modest clinic in Fort Payne, Alabama, he was the second of three kids raised on a family farm hugging the flanks of Lookout Mountain. Life was simple, sacred: mornings milking cows, afternoons chasing cousins through pine thickets, evenings filled with gospel quartets echoing from the clapboard church. Music seeped in early—Owen and his kin, Teddy Gentry and Jeff Cook, strumming borrowed guitars to the twang of Hank Williams on a crackling radio. “We’d sing till the stars came out,” Owen later reminisced, his drawl curling like woodsmoke. By high school, the trio had formed Wildcountry, a ragtag outfit gigging at sock hops and county fairs, their sound a gumbo of country, rock, and R&B that turned heads in a town more fond of football than fiddles.

The grind was real. Owen dropped out in ninth grade to help on the farm, only circling back to graduate in 1969 before earning an English degree from Jacksonville State University in 1972. But academia couldn’t cage his spirit; by ’73, the cousins had decamped to Anniston, pooling $4,000 to chase Nashville dreams. Rejections stung like yellow jackets—labels called them “too rock for country”—so they honed their craft at Myrtle Beach’s Bowery club, slinging 13-hour sets six nights a week for tips and beer. It was there, amid the haze of cigarette smoke and spilled Schlitz, that “Alabama” stuck as a moniker, fans hollering for “those boys from Alabama.” Drummer Mark Herndon joined in ’79, and by 1980, RCA inked the deal on the strength of “My Home’s in Alabama,” a Gentry-Owen ode to roots that hit No. 17 and lit the fuse.

What followed was a supernova. Alabama’s debut album, Wildcountry (retitled for radio), birthed “Tennessee River,” their first No. 1 in 1980, kicking off a streak of 27 chart-toppers that redefined the genre. They weren’t solo crooners in Stetsons; they were a band—self-contained, electric, with Owen’s rhythm guitar locking into Cook’s leads and Gentry’s bass thrum, Herndon’s kit driving like a semi on I-65. Hits cascaded: “Feels So Right” (1981, their first pop crossover at No. 37 on the Hot 100), “Mountain Music” (1982, a foot-stomper evoking Appalachian euphoria), “Dixieland Delight” (1983, college football’s unofficial anthem), “If You’re Gonna Play in Texas (You Gotta Have a Fiddle in the Band)” (1984, a two-step tour de force). By mid-decade, they’d notched 21 consecutive No. 1s, outselling the Beatles on country charts, their youthful vigor—Owen’s soaring tenor, the band’s harmonies like kinfolk at a reunion—drawing teens to fairs and arenas alike.

The impact? Seismic. Alabama shattered the solo-star mold, proving groups could thrive in Nashville’s boys’ club, broadening country’s tent to include rock edges and pop sheen. They racked 75 million albums, 21 gold/platinum/multi-platinum LPs, two Grammys, 12 ACMs, 20 AMAs, and Entertainer of the Decade in 1989. Inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2005, they earned the RIAA’s Country Group of the Century nod in 1999. Offstage, Owen’s faith-fueled philanthropy shone: launching Country Cares for St. Jude in 1989, raising $80 million-plus for kids’ cancer fights; his 3,000-acre Tennessee River Ranch a haven for family and Herefords. Even after retiring from full-time touring in 2004 (reuniting sporadically), Owen’s pen never dulled—co-writing “Forever’s as Far as I’ll Go” (1990) and penning memoirs like Born Country (2011), a testament to faith, family, and fiddle strings.

Enter Shelton and Bryan, the torchbearers who’d grown up idolizing Owen’s every riff. Blake Tollison Shelton, born June 18, 1976, in Ada, Oklahoma, to a used-car dealer dad and beauty-shop mom, lost his half-brother in a car wreck at 14, channeling grief into guitar strings. Moving to Nashville at 17 with $500 and a demo tape, he scraped by on construction gigs before “Austin” topped charts in 2001, launching 28 No. 1s like “God’s Country” and “Honey Bee.” A 23-season Voice coach (winning nine times), Shelton’s bro-country blueprint—beer-soaked hooks, everyman charm—has sold 60 million records. Married to Gwen Stefani since 2021, his Ole Red empire spans seven spots, from Tishomingo to Vegas, blending barstools with backbeats.

Luke Bryan, born July 17, 1976, in Leesburg, Georgia, to a peanut-farmer dad, endured tragedy young—brother Chris’s 1996 death derailing his Nashville move till 2001. Discovered by producer Allen Boyd, “All My Friends Say” (2007) ignited 25 No. 1s, from “Country Girl (Shake It for Me)” to “One Margarita.” A Voice alum turned Idol judge since 2022, Bryan’s farm-boy flair—hunting tales, beach anthems—has moved 100 million units. Widowed young (wife Caroline post-ovarian cancer), he’s a dad to two, his farm life fueling tracks like “Huntin’, Fishin’ and Lovin’ Every Day.”

Their bromance? Legendary—roasts at awards, duets like “Hillbilly Bone” (2009), and Voice battles that birthed viral gold. At BMI, their “Mountain Music” was no lark; it was lineage. Bryan had solo’d “Feels So Right” earlier, his velvet baritone sultry over piano swells, drawing misty cheers. Riley Green preceded with “My Home’s in Alabama,” acoustic and aching, Mickey Raphael’s harp sighing like a summer breeze. Video missives from Dolly Parton (“Randy, you’re the heart of the South”) and Kenny Chesney (“Your sound’s in my blood”) set the table, but Shelton and Bryan’s romp was the feast—rowdy, reverent, a toe-tappin’ torrent that had Owen beaming through blurs.

Post-performance, the afterparty at BMI’s rooftop hummed with replays on phones, Owen cornered by well-wishers: “You boys just made 40 years flash by.” Shelton clapped his back: “Randy, you wrote the map—we’re just followin’.” Bryan, arm around Owen’s shoulder, quipped, “Next up: you guest on my farm tour.” Social scrolls lit up—clips amassing 5 million views, fans tweeting “Tears and two-steps—pure country soul” and “Owen’s the godfather; these guys the sons.” For Owen, the Icon Award—joining Toby Keith, Loretta Lynn, Willie Nelson in BMI’s pantheon—was validation after decades of doubt. “Songs change lives,” he said, voice steady now. “Mine changed mine.”

In Nashville’s relentless churn, where hits hatch overnight and heroes fade fast, that night stood eternal—a bridge from Owen’s Bowery beginnings to Shelton and Bryan’s stadium roars. It wasn’t mere music; it was memory made manifest, a thank-you etched in harmony. As the chandeliers dimmed and the crowd spilled into the neon night, one chord lingered: country’s family, forged in fire and fiddle, sings on—united, unbroken, forever fine.