In the vast, unforgiving expanse of South Australia’s outback, two disappearances have gripped the nation, sparking widespread speculation and fear. Four-year-old Gus Lamont vanished from his family’s remote sheep station on September 27, 2025, prompting one of the largest search operations in the state’s history. Just one day earlier, on September 26, a 40-year-old man named Benjamin went missing in the same rugged region, his vehicle found abandoned the following day—the very day Gus was last seen. While authorities insist there is no evidence linking the cases, the eerie timing and proximity have fueled rumors of a sinister connection, leaving communities on edge and investigators probing every possibility. As the search for Gus concludes without resolution, questions linger: Could these events be more than coincidence?

Gus Lamont’s disappearance has captured hearts across Australia and beyond. The young boy, described as shy but adventurous with long, blond curly hair and brown eyes, was last spotted around 5:00 p.m. on September 27 at Oak Park Station, a sprawling sheep farming property about 40 kilometers south of Yunta in South Australia’s Mid-North. This isolated homestead, roughly 300 kilometers northeast of Adelaide, is emblematic of the outback’s harsh beauty—endless plains dotted with saltbush, rocky outcrops, and sparse vegetation that can conceal secrets in its folds. Gus was playing unsupervised on a mound of dirt near the family home while his grandmother tended to his younger brother inside. After about 30 minutes, she returned to call him for dinner, only to find him gone. His mother, Jess Lamont, and a grandparent were attending to sheep 10 kilometers away, while his father, Josh, lived two hours from the property and was not present.

The family searched for three hours before notifying police, a delay attributed to the property’s immense size but one that experts say may have complicated early efforts. Gus was wearing a grey sun hat, a blue long-sleeved Minion T-shirt, light grey pants, and boots—attire that should have stood out against the arid landscape, yet nothing has been recovered. South Australia Police have described the case as heartbreaking, with the family cooperating fully and supported by victim services.

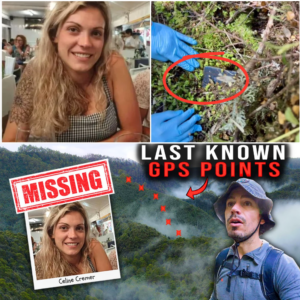

Meanwhile, Benjamin’s case unfolded in a similarly remote area, adding layers of intrigue. The 40-year-old was last seen on September 26 driving erratically along the Stuart Highway between Port Augusta and Glendambo, a stretch of road known for its isolation and heavy truck traffic. Several truck drivers reported his blue 2006 Hyundai Getz, bearing Western Australia plates, weaving unpredictably. The vehicle was discovered abandoned in dense scrubland near Wirraminna, about 10 kilometers off the highway, on September 27—the same day Gus disappeared. Little is known about Benjamin’s background; no surname has been publicly released, and details about his family or reasons for being in the area remain scarce. Police have shared his image, depicting a man with disheveled hair and a weathered appearance, urging anyone with information to come forward.

The locations, while not adjacent, are within the same outback expanse. Yunta lies east of Port Augusta, while Glendambo is north along the Stuart Highway, approximately a two-hour drive apart, though actual distances suggest a longer journey via connecting roads. This proximity, combined with the temporal overlap—Benjamin vanishing the day before Gus, his car found on the day of Gus’s disappearance—has ignited public speculation. Online forums and social media buzz with theories: Could Benjamin have encountered Gus? Was there foul play involving both? Or is it merely the outback’s cruelty claiming two lives independently?

Search efforts for both cases highlight the formidable challenges of the terrain. For Gus, an initial 10-day operation covered 470 square kilometers, involving state emergency services, drones, helicopters with infrared, Aboriginal trackers, Australian Defence Force personnel, all-terrain vehicles, and volunteers. Scaled back on October 7, it resumed on October 14 with 80 soldiers walking 20-25 kilometers daily amid extreme heat over 34°C and 50 km/h winds, but ended on October 17 with no new leads. The case shifted to recovery, handled by a dedicated taskforce. Similarly, Benjamin’s search involved police, emergency services, drones, and trackers in rough, canopy-covered scrub. Footprints were found but led nowhere, and the effort was scaled back on October 3. Police continue appeals for dashcam footage from the Stuart Highway on September 26.

Authorities maintain no foul play in Gus’s case, theorizing he wandered off and succumbed to the elements. For Benjamin, the erratic driving suggests possible distress, but details are limited. A senior police official stated, “We don’t have anything that indicates a link at this point in time but we’re leaving every option open.” A police spokesperson confirmed they are not investigating any connection. Yet, experts urge thoroughness, noting minute details can be overlooked in vast areas and suggesting reinterviewing witnesses and ground-level searches.

Public response has been intense, with volunteers aiding searches and online speculation rampant. Fake images of Gus being abducted have circulated, prompting police warnings. Some express frustration over resources, criticizing appeals for Benjamin amid Gus’s search scaling back. The Lamont family shared their anguish: “Gus’s absence is felt by all of us and we miss him more than words can express.” No similar statement from Benjamin’s kin has surfaced.

These cases echo historical outback mysteries, like the Beaumont children in 1966, underscoring the region’s dangers—extreme weather, wildlife, and isolation. As investigations continue, the outback’s silence amplifies the pain. Police vow unwavering determination for closure. Whether linked or not, the dual tragedies remind us of nature’s indifference and the fragility of life in Australia’s remote heart.