Amid the pristine peaks of the Swiss Alps, where luxury ski resorts draw crowds seeking winter thrills, a 16-year-old Parisian teenager named Axel Clavier recently revisited the scorched site of Le Constellation bar, the epicenter of a catastrophic New Year’s Eve fire that killed 40 people and left scores injured. The blaze, which tore through the popular basement venue in the early hours of January 1, 2026, transformed a night of celebration into a harrowing ordeal of survival and loss. Clavier, who ingeniously used an overturned table as a shield before shattering a window to escape, recounted losing nine friends in the chaos—a personal toll that plunged him into months of denial and emotional turmoil.

The incident unfolded in Crans-Montana, a glamorous alpine town known for its high-end chalets and vibrant nightlife. Le Constellation, a cavernous bar with a basement dance floor and an upstairs area for watching sports, was a hotspot for young locals and tourists. On New Year’s Eve, the venue was teeming with revelers, many in their teens and early 20s, drawn by free entry for those under 18 and a lively atmosphere fueled by music and drinks. Reports indicate the bar was at or near capacity, with estimates of up to 300 people inside when disaster struck around 1:30 a.m.

Eyewitnesses and preliminary investigations point to a festive stunt gone awry as the spark. A bartender reportedly lifted a female colleague onto his shoulders while she held a champagne bottle topped with flaming sparklers. The flames quickly ignited the wooden ceiling, decorated with flammable materials, leading to a rapid spread of fire. “It was like a flash,” survivor Noa Bersier told Swiss media outlet Le Temps. “One moment we were cheering, the next the ceiling was ablaze.” The low ceilings and narrow exits exacerbated the situation, creating a deadly bottleneck as panicked patrons rushed for the stairs. Thick smoke filled the space, causing asphyxiation and disorientation, while the heat intensified into a flashover, where superheated gases ignite simultaneously.

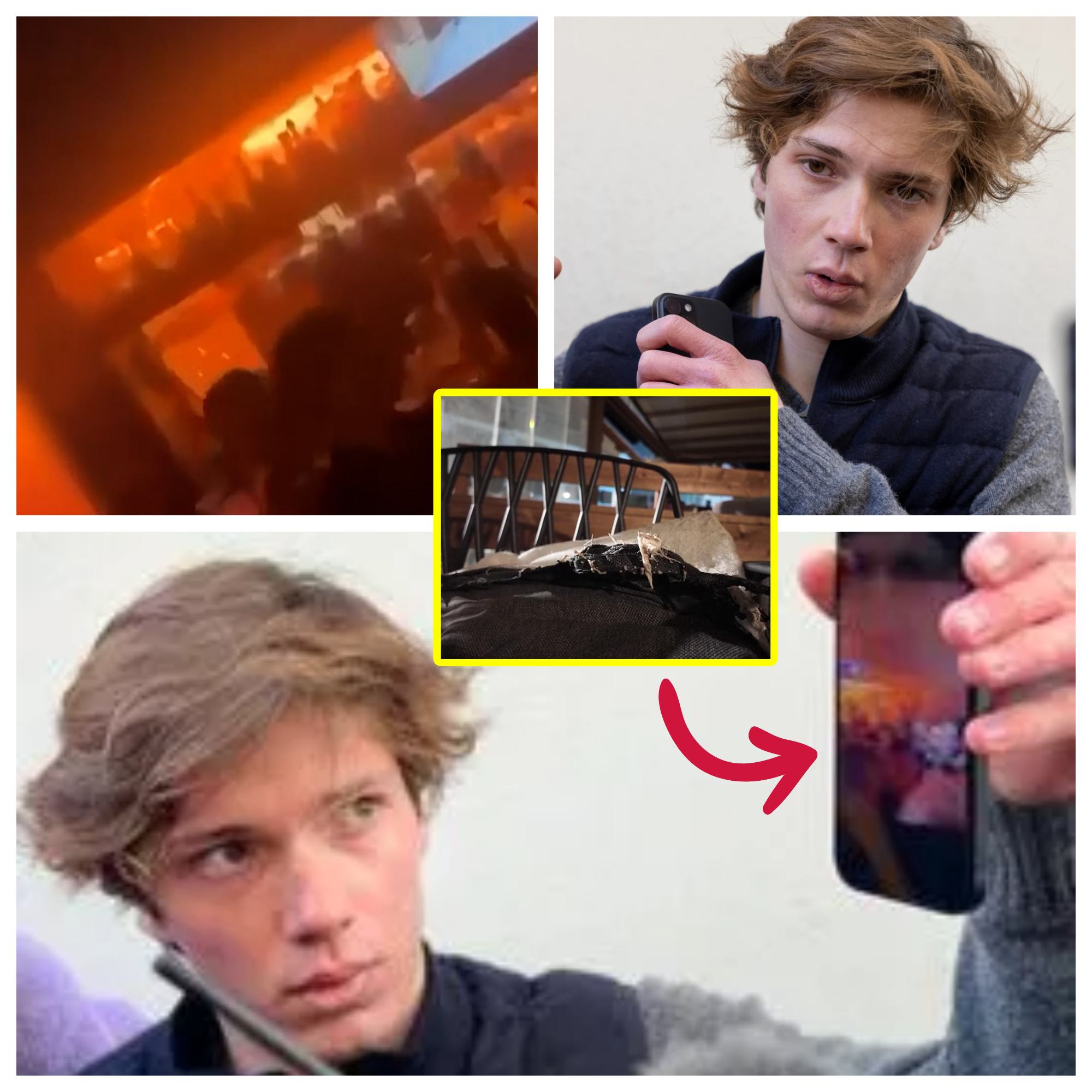

In the midst of the pandemonium, Clavier’s quick thinking saved his life. The teenager, visiting from Paris with a group of friends, described pulling a nearby table toward him and flipping it over to act as a barrier against the encroaching flames. With no viable exit in sight, he then smashed through a plexiglass window and clambered to safety. “Instinct just kicked in,” Clavier shared in an interview with French broadcaster BFMTV. “I couldn’t see anything through the smoke, but I knew I had to get out.” His escape was one of the few success stories that night, but it came at a steep price: nine of his companions, part of the same social circle, did not make it out alive.

Clavier’s return to the site, marked by a somber gathering of flowers, candles, and photos of the victims, highlighted the ongoing psychological scars. Standing near the bar’s ruins, now a stark reminder amid the snowy landscape, he opened up about the aftermath. “For months, I was in total denial,” he said. “The shock made everything feel unreal—the screams, the heat, the loss. It was like watching a movie about someone else.” Mental health experts consulted by authorities note that such responses are typical in survivors of mass tragedies, often evolving into complex grief, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Clavier’s experience echoes that of other survivors, like 19-year-old Ferdinand Du Beaudiez, who ran back into the flames to save his brother and girlfriend, only to witness horrors that continue to haunt him.

The victims represented a cross-section of youth from across Europe. Confirmed fatalities included Swiss teens aged 16 to 21, Italian visitors such as 16-year-old Chiara Costanzo and golfer Emanuele Galeppini, and others from France and beyond. Families endured heart-wrenching uncertainty in the days following the fire. Laetitia Brodard, mother of 16-year-old Arthur Brodard, described her desperate search: “His body is somewhere,” she told reporters outside a makeshift morgue. Andrea Costanzo, Chiara’s father, lamented to Italian media, “She had so many dreams ahead.” The youngest victim identified was 14, underscoring the bar’s appeal to underage partygoers. DNA testing was required for many identifications due to severe burns, adding to the families’ anguish.

First responders arrived swiftly—police logs show calls at 1:32 a.m.—but the fire’s ferocity overwhelmed initial efforts. Over 40 emergency vehicles and 10 helicopters descended on the scene, with firefighters battling flames that turned the bar into an inferno. Bystanders heroically assisted, breaking windows to rescue trapped individuals and using improvised tools like curtains to shield the injured from the cold. A nearby UBS bank branch served as an impromptu medical hub, its furniture cleared for triage. Hospitals in Sion and Zurich treated dozens, with 22 patients aged 16 to 26 admitted for burns and smoke inhalation. Gianni Campolo, a 19-year-old who helped pull people out, recounted to ABC News: “I’ve seen horror, and nothing compares. People were burned beyond recognition.”

The Valais cantonal prosecutor’s office, led by Attorney General Beatrice Pilloud, is spearheading a probe into potential criminal negligence. While arson has been dismissed, scrutiny falls on the bar’s management for possible safety lapses, including inadequate fire extinguishers, overcrowding, and the use of pyrotechnics indoors. “All hypotheses are being examined,” Pilloud stated at a briefing. Social media videos circulating online show flames erupting from sparklers, fueling speculation about preventable risks. The venue’s owners face preliminary charges, and experts are reviewing building codes, which in Switzerland mandate strict fire safety but may have been overlooked.

This tragedy draws parallels to other nightclub fires, such as the 2017 Grenfell Tower inferno in London or the 2003 Station nightclub fire in the U.S., where pyrotechnics ignited foam insulation, killing 100. In Europe, the 2015 Colectiv club fire in Bucharest, Romania, which claimed 64 lives due to similar issues, led to widespread reforms. Swiss officials, including President Guy Parmelin, have vowed similar action. “This is a national sorrow,” Parmelin declared, ordering flags at half-mast for five days. Calls for banning indoor fireworks and enhancing youth venue inspections have gained traction in parliament.

Community response in Crans-Montana has been one of solidarity. Vigils attract thousands, with tributes piling up outside the bar. Local businesses have donated to victim funds, and counseling services are ramped up through the Swiss Red Cross. For young survivors, programs focus on peer support groups to address isolation. Eliot Thelen, another teen survivor and Italian football prospect, shared with Luxembourg Times: “I thought it was all over. Now, every day is about rebuilding.”

Clavier’s story, from his daring escape to the denial that followed, exemplifies the dual edges of survival—physical triumph shadowed by emotional wreckage. As he stood at the site, reflecting on the friends lost, he emphasized moving forward: “They wouldn’t want me to stay stuck in that night.” Yet, with investigations ongoing and lawsuits looming, closure remains elusive for many.

The Le Constellation fire serves as a grim cautionary tale in an era of packed nightlife venues. As Switzerland grapples with the fallout, the focus shifts to prevention, ensuring such a blaze never repeats. For Clavier and others, the path to healing is long, but their resilience offers a glimmer of hope amid the ashes.