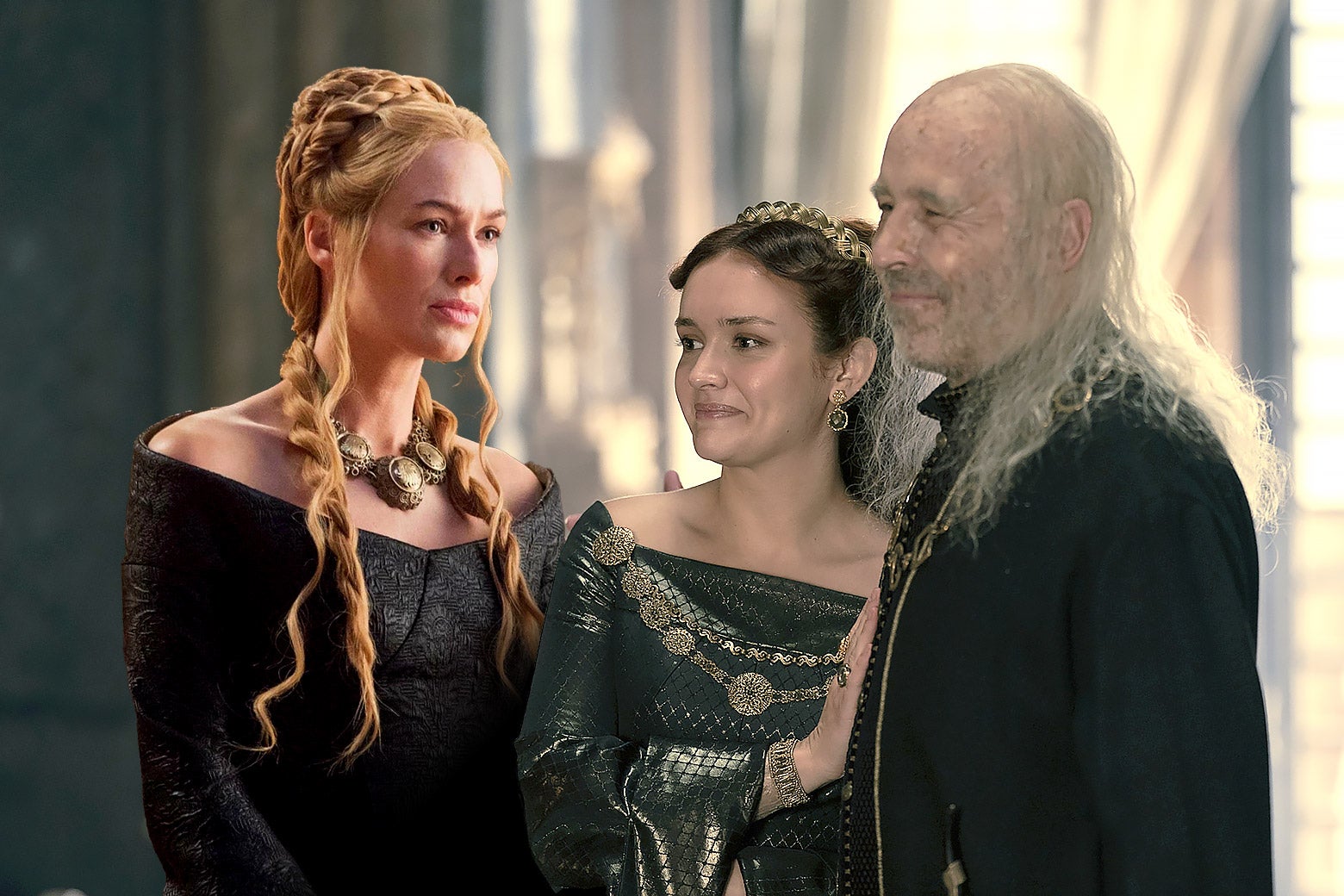

The woman-centered spinoff has yet to produce a character as compelling as Game of Thrones’ cold-hearted queen.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by HBO.

Six episodes into House of the Dragon, HBO’s Game of Thrones prequel about the dragon-riding Targaryen dynasty that is really about the headaches of a blended family, I find myself in a place I never expected to be: I miss Cersei Lannister. Cersei! The queen who orchestrated Robert Baratheon’s and Ned Stark’s deaths, who gaslit Sansa and raised Westeros’s most monstrous teenager. The woman who turned mass murder into a side hobby. I’m like, she would really feel like a breath of fresh air here.

It’s not for the obvious reasons, like Lena Headey’s astonishing performance, or even nostalgia for the early seasons of Thrones, which had none of the CGI and all the subtlety and deftness that HotD lacks. The truth is, I miss Cersei’s competence. I miss her experience; her sense of how a court and alliances work; and her knowledge that power is not simply conferred upon you. I miss—and yes, I’m amazed to be writing this—her feminism, her refusal to surrender to the limits of what women in Westeros were allowed to be. With House of the Dragon’s depiction of female protagonists as wide-eyed naifs or entitled whiners, the show has done the impossible—it’s made Cersei’s brutal, blood-soaked rise feel, in comparison, like breaking a glass ceiling.

House of the Dragon is purportedly the more feminist show, with its female characters getting the most screentime by far. It’s also, like Bridgerton, stone-cold serious about the risks of childbirth, which I for one appreciate, even if those depictions are hard to watch. But as many have noted, it seems to have learned all the wrong lessons from late-season criticism of Thrones, doubling down on violence for violence’s sake. On top of that, it has a serious protagonist problem, one that undermines its feminist bona fides.

Princess Rhaenyra, daughter of King Viserys, is named heir to the Iron Throne when her mother and infant brother die following a forced C-section. In a kingdom where a queen has never sat on the throne, this could be interesting territory, a chance for Rhaenyra to build support and work with her father who, while seen as a weak ruler, backs her claim with a consistency he shows with nothing else. Instead, she sulks and withdraws, hurt when her father chooses her close friend and the daughter of the King’s Hand, Alicent Hightower, as his second wife. That’s understandable, but the sympathy we have for her is squandered by the fact that she is straight-up insufferable.

This week’s episode, following a 10-year time jump that recast the actors for Rhaenyra, her husband Laenor Valaryon, and queen Alicent Hightower, could be the start of a course correction; time will tell. But so far, all Rhaenyra has done is act entitled to the throne while doing nothing to build alliances, gain support, or learn statecraft. For several years she refuses to marry, which I get, but if you want to rule Westeros you need a strong political alliance, and her father allows her to choose her own husband, a freedom few women in Westeros enjoy. Instead she mopes over a wrong that hasn’t even come to pass—the assumption that Viserys will cave and name his son Aegon heir—instead of trying to strengthen her position.

The most selfish decision she makes reverberates in ways that will threaten her family. She seduces and then spurns her sworn protector Ser Criston Cole (who not for nothing, asks her to stop), putting his life in danger and destroying his sense of worth in the process. This drives him to Alicent’s side, where he becomes a powerful ally against her.

Cersei was awful, but she never expected anything to be handed to her. It’s difficult to watch Rhaenyra complaining about how hard it is to be a princess and not think wistfully of Cersei sitting on the Iron Throne, wearing the leather warrior gown that launched a thousand power-dressing memes. It’s a moment born out of ashes—Cersei has lost her three children, the engine behind her ruthlessness, and so nothing is left except to take power for herself. Lena Headey,brilliantly, forces you to hold two truths—that Cersei is terrible, and that she has suffered. Perhaps the knowledge that Cersei is right about how dangerous the world is, even if she is wrong about how to respond to it, is what makes her so much more interesting to watch than Rhaenyra, pouting about injustices that haven’t even happened.

This week’s time jump offers the potential for a reset. The opening shot shows Rhaenyra giving birth to her third son, then being told that the queen wishes to see the baby immediately. Clearly a power play is at work, and Rhaenyra grits her teeth, gets dressed, and hobbles to the queen’s chambers, trailing blood. It’s all filmed in long takes, like the kitchen scene in Goodfellas, and watching the princess force herself forward out of sheer will was the first time she gained my total respect. If you can do that after a Westerosi home birth, you probably have what it takes to sit on the Iron Throne.

The trouble is, despite fast forwarding ten years, it still feels like the characters are following the same old playbook. Rhaenyra does not seem to have built alliances or support at court, or understand just how poisoned Alicent is against her. Alicent, for her part, still seems to be offended that her friend lied to her about her chastity a decade ago (I’m serious), in part because it led to her father being dismissed as Hand of the King. Alicent’s obsession with Rhaenyra’s virtue is just plain weird, but Rhaenrya’s naivete in leaving herself open to harmful gossip strains belief for a woman who grew up at court. While she denies it, she is having an affair with Ser Harwin Strong, the head of the City Watch, and her children are most likely his. (They, at least, quite visibly not her husband’s.) She seems not to understand the point that everyone else grasps—her father’s intentional blindness is what protects her, and without him, her family is in danger. It doesn’t help thatHouse of the Dragon’s main plot tensions revolve around who Rhaenyra is or isn’t sleeping with; whether this is supposed to represent her rebelliousness or boundary pushing, I don’t think it makes the point the show thinks it does.

As for Alicent, she is now fully turned against her childhood friend, aware that her sons pose a threat to Rhaenyra’s succession. She tries to fashion herself as a court player with influence but doesn’t actually grasp what that means; she’s playing at the game of thrones, but Cersei or Lady Olenna would have eaten her alive. When she tells Larys Strong—a Littlefinger in the making—that she wants her father back as Hand, she obviously doesn’t expect him to literally murder the Hand and his son, who happen to be his own father and brother, because that’s dark even for Westeros, but her horrified protests after the fact fall a bit flat. She brought Larys into the fold because she knows he puts ambition above everything else. What did she think would happen?

You could ask Cersei, because she would know. As she says to Ned, “When you play the game of thrones, you win or you die. There is no middle ground.” Nothing on House of the Dragon feels remotely close to those stakes.