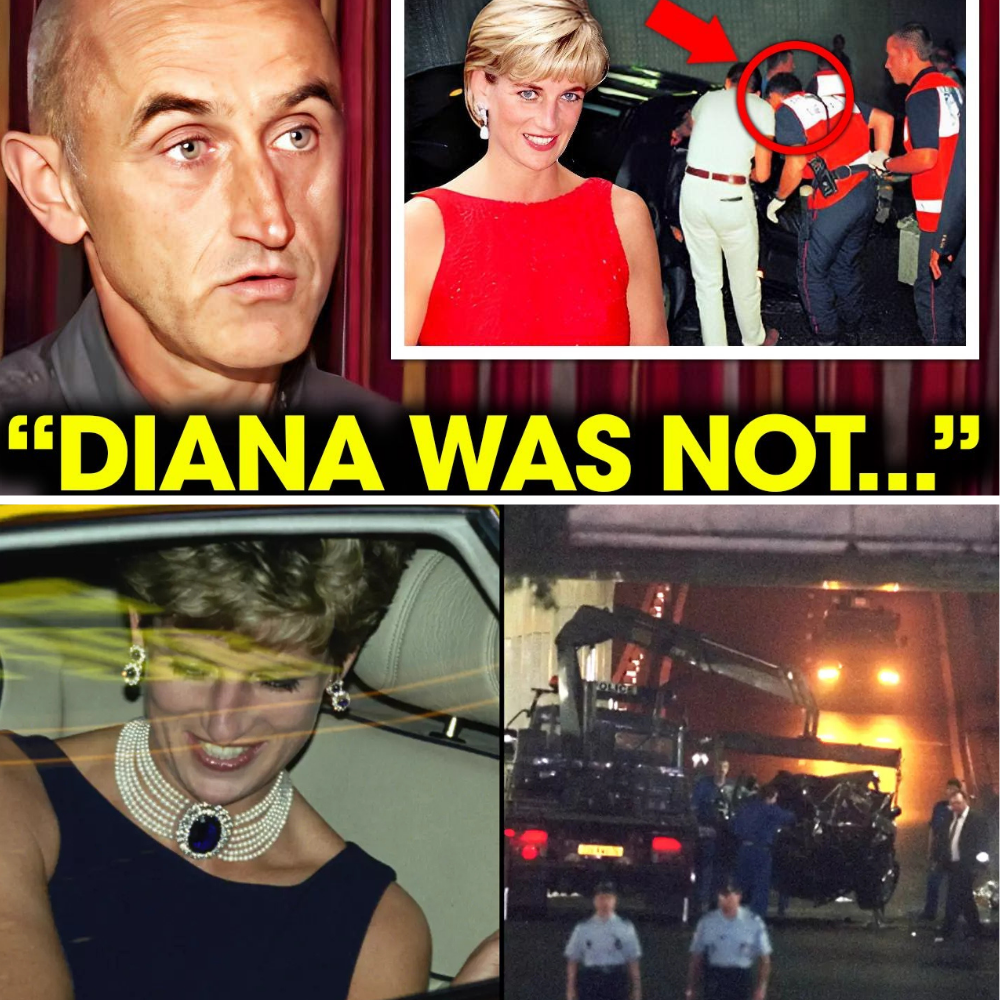

Paris, August 31, 1997. The Pont de l’Alma tunnel, a shadowed artery under the City of Light, became a tomb for icons. A black Mercedes S280, fleeing paparazzi flashes like ghosts in the night, slammed into pillar 13 at over 60 mph. Driver Henri Paul, blood alcohol levels twice the legal limit, perished instantly alongside passenger Dodi Fayed, son of billionaire Mohamed Al-Fayed. In the wreckage’s twisted embrace lay Trevor Rees-Jones, the bodyguard, battered but breathing. And there, in the back seat, was Diana, Princess of Wales – 36, radiant, rebellious – her world unraveling in seconds.

For 28 years, the world has pieced together that fatal puzzle: a high-speed chase from the Ritz Hotel, no seatbelts in the rear, a white Fiat Uno’s phantom role, conspiracy whispers of royal foul play. Official inquiries – Britain’s 2008 inquest, France’s Operation Paget – ruled it an accident, fueled by reckless driving and pursuit. Yet the human heart of the horror remained veiled, guarded by oaths unspoken.

Enter Xavier Gourmelon, the firefighter whose gloved hands first cradled royalty in ruin. At 42 then, now 70 and retired, Gourmelon led the first response team, arriving in under three minutes. “It was chaos, but routine at first,” he recalls in a voice cracked by time and tears. No blood marred her at the scene – just a slight shoulder graze, eyes wide with shock. He pulled her free, held her hand, felt her pulse flicker. “She was alive, conscious. She squeezed my fingers, looked right at me.” Her words, soft as a sigh: “My God, what’s happened?” Not a scream, not panic – grace amid the grind of metal.

Gourmelon massaged her heart when it stuttered into arrest, coaxing breath back with CPR. “I thought we’d saved her. She seemed stable.” Oxygen administered, she was stretchered away to Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, four miles and a lifetime distant. There, internal hemorrhaging from torn veins claimed her at 4 a.m. – not the crash’s immediate fury, but a slow, savage bleed.

Why the silence? “Someone ordered me quiet that very night,” Gourmelon confesses now, eyes welling in a dimly lit Paris café. Not superiors, he implies, but shadowy figures – perhaps security, perhaps higher – who impressed upon him the weight of discretion. “They said it was for the family’s sake, for stability. I was young, dutiful. I obeyed.” Bound by fire service protocol until retirement, he spoke once at the 2008 inquest, but held back the raw intimacy. No media, no memoirs – until grief and conscience collided on this 28th anniversary.

His tearful admission shatters the narrative’s edges. Diana wasn’t a broken doll in the dark; she was aware, afraid, human. “She trusted me in that moment,” he says, voice breaking. “I see her eyes still – blue, bewildered.” It humanizes the myth: the “People’s Princess,” who hugged AIDS patients and landmine victims, reduced to vulnerability in a stranger’s arms. Conspiracists pounce – was the delay to the hospital deliberate? Rees-Jones, sole survivor, remembers little; Paul’s intoxication was no secret, yet the Fiat’s driver vanished like smoke.

Gourmelon’s legacy? Not scandal, but solace. “She wasn’t just a princess; she was a mother, a fighter.” His words invite reflection: Diana’s death birthed global grief, anti-landmine campaigns, her sons’ mental health advocacy. William and Harry, now fathers, carry her torch – Harry in Invictus Games, William in homelessness fights. Yet the tunnel echoes on, a reminder that even icons whisper farewells.

In breaking silence, Gourmelon honors the woman, not the wreckage. “I wish I’d said more sooner,” he murmurs. Twenty-eight years later, Paris’s shadows yield one more truth: Diana died asking questions, leaving us to answer them.